Are central banks diversifying away from the dollar?

More on:

Opinion -- informed opinion -- is divided.

The currency team at the Bank of New York says yes. Simon Derrick wrote on Monday:

"our own view [is] that one of the driving forces behind the EUR’s sustained strength over the past six years has been reserve diversification (FX reserves globally have all but tripled since the first quarter of 2002)"

Bernhard Eschweiler-- the head of JP Morgan's Central Bank Group -- says no. He wrote in the FT:

the idea that central banks are undermining the dollar makes neither sense nor is there evidence in the data.

Why? Countries that manage their exchange rate against the dollar are, according to Eschweiler, forced to hold dollars.

The principle mistake that many commentators make is the assumption that central banks can separate the currency allocation of reserves from their exchange rate objectives. In practice, this is often not the case, especially for the large surplus economies in Asia as well as the oil-exporting countries. These countries all follow some sort of dollar standard, whether it is an outright peg or a dirty float.

So, when they intervene to prevent their currencies from appreciating against the dollar, they get mostly – or even exclusively – dollars (also because most of their trade and capital flows are dollar denominated).

However, it is difficult to sell those dollars back to the market without causing renewed dollar weakness and, thus, trigger new interventions. Some small central banks may get away with it, but not the group of large reserve holders. There is no free lunch: if you shadow the dollar you also have to hold it. (emphasis added)

I tend to agree with Mr. Eschweiler. Here is why --

The IMF's data on global reserves provides the starting point for any analysis. Many central banks report data on the currency composition of their reserves. And the IMF sums up all the national data and releases the aggregate sums. That data though has one major drawback -- about half of global reserve growth currently comes from countries that do not reporting data on the currency composition of their reserves to the IMF. The countries also account for a rising share of the global stock of reserves.

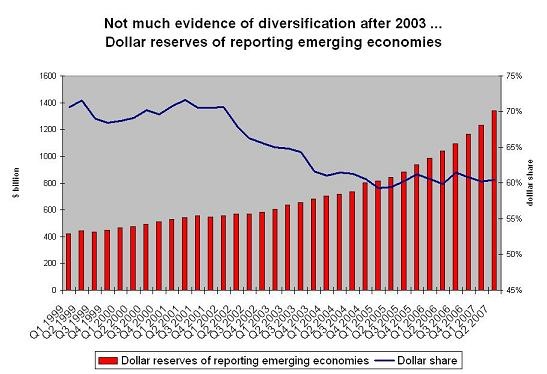

Nonetheless, it is useful to take a look at what those central banks that do report data have been doing. The following chart plots their total holdings of dollars v the dollar share of their reserves.

The data here is quiet clear. Those emerging economies that report data on the currency composition of their reserves to the IMF did diversify their reserves between early 2001 and the end of 2004. Since the end of 2004, though, the dollar share of these countries reserves has been constant. And their total dollar holdings have increased quite sharply -- they are up by roughly $500b since the end of 2004.

This data consequently suggests that diversification played a bigger role in the dollar's 2003 and 2004 slide than in its 2006 and 2007 slide.

One caveat: I doubt the IMF data captures various balance sheet hedges that central banks may have used to reduce their effective dollar exposure. I have no good way of judging the magnitude of such hedges.

The IMF data here also poses a bit of a puzzle, one that I have discussed before.

Russia almost certainly reports the currency composition of its reserves to the IMF (Russia discloses this data publicly, so there is little reason not to report it to the IMF). Russia very clearly reduced the dollar share of its reserves in early 2006. That reduction though doesn't show up in the aggregated data, probably because a set of countries with a very high dollar share have been adding to their reserves very rapidly. Brazil is the obvious candidate.

The IMF doesn't say who reports data on the currency composition of their reserves and who doesn't. But I am certain that China does not report data on the currency composition of its reserves to the IMF, and suspect that the GCC central banks do not either. That is an important gap, as, to quote Mr. Derrick:

"any potential shift in demand from the largest reserve accumulator of all should not be ignored"

So what have China and the Gulf been doing.

Mr. Eschweiler argues that China hasn't been able to reduce the dollar share of its reserves, and may even be increasing the dollar share. The US data, of course, doesn't show such an increase, but as Eschweiler notes, the US data doesn't capture Chinese purchases from banks in Europe and Asia.

And, more crucially, Eschweiler argues that China observed sale of dollars in the market do not seem to have been large enough to keep the dollar share of its reserves from rising. Eschweiler:

A different perspective suggests that China may actually struggle to keep the dollar share from rising since all of its interventions take place in dollars. Over the first half of the year, China’s reserves grew by $270bn.

Thus, to keep the share of dollars at 70 per cent, which is the level most experts agree on, China would have had to sell more than $3bn per week. This is not impossible, but would have stirred up much more market interest than has been observed.

Interesting.

I would note that some of the rapid increase in China's reserves in the first half of 2007 came from the unwinding of swap contracts with the banks and another portion represents valuation gains, so the actual increase in China's foreign assets in the first half was probably somewhere between $200 and $250b, not $270b. But Eschweiler's basic point still holds.

What of the other key part of the dollar zone, the oil-rich countries in the Gulf?

Here there is an added complication. China's reserves are -- really were -- essentially managed by a single institution, the State Administration of Foreign Exchange. And SAFE reports to the central bank. Up until now, there wasn't much of an issue of policy coordination. The institution that implemented the country's exchange rate policy also managed its foreign assets.

The Gulf's official assets, by contrast, are not managed by a single institution. Each country manages its own assets, and most Gulf countries have both a sovereign wealth fund as well as a central bank. The Emirates has two sovereign wealth funds (one for Abu Dhabi and one for Dubai), "private" fund for Dubai's sheik, a central bank and is considering setting up an Emirati wealth fund as well. There are ten or so government run institutions managing over $10b in foreign exchange. Three manage over $200b -- Abu Dhabi's Investment Authority (ADIA), Kuwait's Investment Authority (KIA) and the Saudi central bank (SAMA).

Policy coordination is a real challenge.

Rachel Ziemba and I estimate that the smaller GCC countries -- the ones with sovereign wealth funds, transfered roughly $85b of oil revenues to their funds in 2007. ADIA also reinvests the income and on its existing assets and some smaller funds increased their assets under management by borrowing a bit more -- so total official asset growth likely will be a bit higher.

Let's say $30b of that was invested in the US. That is just a guess -- I certainly am not privy to the Gulf's portfolio allocation. However, it is an informed guess: sovereign wealth funds in the Gulf are widely thought to be diversifying at the margin. In 2006, Rachel and I think these funds received roughly $80b from their countries oil surplus, and perhaps invested $40b in US assets. If we are right, the total US holdings of the Gulf's sovereign wealth funds are going up, but not as fast as before.

The Saudis -- who do not have a formal sovereign wealth fund -- are on track to add about $60b to SAMA's assets in 2007, down from $67b in 2006. Suppose 80% of these flows are in dollars. Their dollar accumulation is down just a bit -- but only a bit. Dollar reserve growth should fall from $50b to $48b.

So has the GCC diversified? Not really.

Why -- we don't yet know how much the smaller GCC central banks (the central banks of the Emirates, Kuwait and Qatar) added to their reserves in 2007, but a reasonably guess would be between $40 and $50b. The Emirates reserves were way up in the first half of 2007, and that was before EVERYONE started betting on a GCC revaluation. In 2006, the reserves of the smaller central banks only went up by $4-$5b or so.

Almost all these reserves are in dollars, so Rachel and I estimate that dollar reserve growth by the smaller GCC central banks increased from around $4b to around $40b.

Total dollar asset growth -- if these numbers are roughly right -- increased substantially. It went from $94b to around $118b. The GCC investment funds diversified. But the GCC central banks bought far more dollars. The region's aggregate exposure to the dollar didn't fall -- even if the institutions holding dollars shifted.

Diversification from the Gulf's sovereign wealth fund has been offset by faster reserve growth by Gulf central banks.

Bottom line: central banks are almost certainly selling a lot more dollars for euros and pounds (and other currencies) than ever before. That is because they are accumulating more reserves than ever before. But the available evidence suggests -- at least to me -- that the overall pace of dollar reserve growth has actually picked up substantially in both the Gulf and in China.

And, by implication, the biggest dollar "overweights" in the world economy are still overweight. There willingness to add to their dollar overweight likely has stabilized the market this year -- meaning the dollar's fall might have been even bigger. But so long as private demand for US assets remains weak and the US external deficit remains large, any shift in their willingness to support the dollar could have major consequences.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store