Can China Become the World’s Clean Energy Leader?

China seems poised to surpass the United States in leading clean energy innovation and climate change response, but Beijing faces internal challenges to energy reform.

April 28, 2017 10:39 am (EST)

- Interview

- To help readers better understand the nuances of foreign policy, CFR staff writers and Consulting Editor Bernard Gwertzman conduct in-depth interviews with a wide range of international experts, as well as newsmakers.

By 2015, China held a third of the global market share [PDF] for hydropower, wind power, and solar energy. The country’s private sector invested $32 billion in 2016 toward international clean energy projects, adding to the $102.9 billion invested a year prior by the government into domestic renewable energy. Many of these investments were made in major developing countries, including Brazil, Egypt, Vietnam, and Kenya.

Investing in clean energy at home also creates opportunities for China to expand its marketing of products such as solar panels abroad, says Jennifer L. Turner, the director of the Wilson Center’s China Environment Forum. China seems poised to surpass the United States in leading clean energy innovation and efforts to mitigate the effects of climate change, but Beijing faces internal challenges to energy reform, she says.

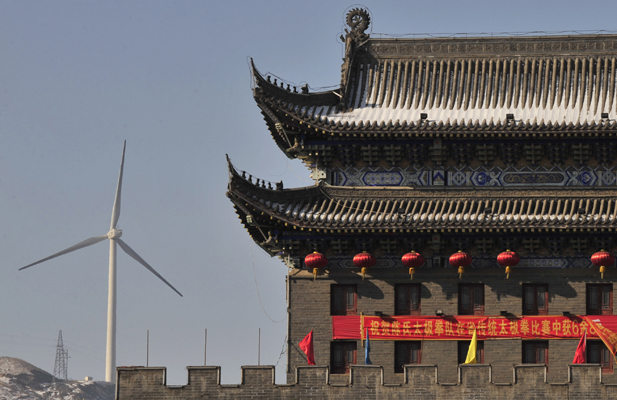

A wind turbine is seen near a gate of the ancient city of Wushu in Diaobingshan. (Sheng Li/Reuters)

A wind turbine is seen near a gate of the ancient city of Wushu in Diaobingshan. (Sheng Li/Reuters)Why are China’s clean energy investments surging?

More on:

The surge has been driven by two primary factors. The first is air pollution. This has become more salient lately, but China was trying to develop more alternatives to coal even before it signed the Paris Agreement. Since then, there’s also been a growing awareness that investing in clean energy development domestically is going to open up more opportunities for China to expand marketing for these products globally. It’s not surprising that China has already captured the global market on solar panels.

“The Chinese investors have a different approach from traditional aid. Their approach is not aid—it is a business opportunity.”

The second factor is energy security. Diversifying energy sources, especially building up clean energy, will be key for China’s energy security, but this has been met with many challenges. For example, Greenpeace released infographics earlier this year that show, by province, the current state of wasted wind power. The high rates of wind power curtailment, which occurs when turbines are shut down so as not to congest transmission lines, reflect a major need for grid reform and reform of the electricity market. Part of it is attributed to growing pains, but they’re also hitting a point where some provinces don’t want to import wind power because they give grid priority to their own local coal-fired power plants, which would generate more profit locally.

Of course, technical problems in integrating more renewables with the grid and local protectionism have slowed actual use of renewables, but the government continues to increase investment. One solution the country has looked to is finding more ways to use solar panels on rooftops rather than rely on faraway solar farms. Additionally, there are efforts underway to encourage solar developments in poorer parts of China, which could help the country take care of its overproduction of solar panels.

Where does the debate between areas that are heavily dependent on coal and more urban areas that want to see improved air quality stand?

China’s Air Pollution Action Plan and revisions to the Air Pollution Prevention and Control Law settled this question for eastern China. The urbanites in these heavily populated east coast cities don’t want coal plants nearby and with new air pollution measures, the government is moving these plants out of the east and reducing coal production. The results of China’s coal use reduction have been striking, as coal-fired power production has dropped for the third year in a row.

While it is encouraging to see coal-fired power is going down, there is another coal industry on the rise. A large number of local governments and provinces in China’s coal-rich western regions started to invest in various coal conversion industries in 2007 or 2008, because turning coal into gas, liquid fuel, and chemicals was more lucrative than coal-fired power. China’s western region will find any way it can to use the abundance of coal, because it is significantly poorer than the east coast.

More on:

Some experts predict that coal use will continue to drop, but the speed will slow down at times as the concern over job loss intensifies. The concern about jobs is what has led the Trump administration to push for bringing coal back despite the lack of market demand. While the United States and China struggle with the coal question, renewable energy jobs in both countries are greater than those in the coal sector.

What roadblocks will the central government face on its clean energy campaign?

“Environmental problems like air pollution have the potential to create destabilization in the country.”

There are technical challenges that are not unique to China. First, current grid systems are not yet able to transfer massive amounts of wind and solar electricity over long distances efficiently, and there is not yet great enough battery technology to store all this power. However, they are putting in super grids, which make transmitting electricity from renewables across long distances easier. These, however, rely on much larger transmission lines cutting through urban areas. With the Chinese government leading the charge in investment, some people anticipate China will make some breakthroughs on the battery technology side. The other challenge, of course, is the unwillingness of the state grid to integrate all this wind and solar. Utility companies like coal because they understand it—it’s easy to use and profitable in the current system.

What is China’s energy strategy? It does everything—coal, gas, renewables, energy efficiency, dams, biomass, biogas. But the government is committed to turning down coal-fired power. The central government was surprised by the coal conversion sector development. A whole industrial sector arose without being led by the central government and it’s not yet well regulated. Most alarmingly, these coal conversion industries produce more CO2 emissions and use much more water than coal-fired plants, so the high amounts of coal pollution and water stress in western China will continue to intensify the area’s vulnerability.

When China’s most recent Five-Year Plan was released in 2016, Greenpeace criticized the Chinese government for setting low goals. Could China do more to decrease its carbon emissions?

Yes, definitely. It will be particularly interesting to see the 2018 [Conference of the Parties] meeting, an important global climate agreement check-in when nations will be required to report on the progress they’ve made in lowering CO2 emissions. China is easily going to meet its commitments early.

That is the moment where hopefully other countries will say in a very collegial way, “you’ve certainly progressed, but you can do even more.” At the World Economic Forum this past January, Chinese President Xi Jinping said China will be the leader on climate and hold to its Paris Agreement commitments. That said, there’s a separate, but also monumental, conversation going on about China’s impact overseas. Paradoxically, Chinese banks and developers are currently supporting the construction of coal-fired power plants in many other countries, like Indonesia and Pakistan.

The U.S. Embassy in Beijing made a daily practice of publishing urban air quality statistics on Twitter. Did this affect public opinion in China?

It was the key in opening the door to public demands for cleaner air. The Chinese public had already become frustrated with air pollution, and seeing the real numbers that were significantly higher than those published by the Chinese government generated a public storm, mainly on social media. But the Chinese government has known since the early 1990s that environmental problems like air pollution have the potential to create destabilization in the country, and the public health crisis was increasingly apparent. The end results were amazingly fast mandates for issuing target [levels of] particulate matter 2.5, the main pollutant in smog, and requiring most large cities to publish real-time air quality data. Within a year of calls by Beijing residents for cleaner air, the Chinese government issued the Air Pollution Action Plan [in 2012] and declared war on pollution. These government actions demonstrated the role that social media plays in increasing public participation to change policies.

How can the United States and China cooperate further on climate and energy?

China’s concern about pollution was a clear driver to increase collaboration with the United States on climate change. Over the past decade I have been intrigued by Chinese NGOs who have been pushing for better enforcement of pollution laws. Ma Jun’s Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs has been a game changer for environmental data transparency and accountability by creating online pollution maps that show exactly how abysmal air and water quality really is. I hosted Ma Jun during his first U.S. exchange tour over ten years ago; he realized information transparency was exactly what China lacked and what drove U.S. campaigns. Climate change, clean energy, and information transparency are some of the areas in which both countries can come together to address common problems, and this kind of interaction can help build vital goodwill between these two often quarreling nations.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Online Store

Online Store