Three Problems with India’s Draft Data Protection Bill

Chinmayi Arun is an assistant professor of law at National Law University in New Delhi and a fellow at the Berkman Klein Center at Harvard University. You can follow her @chinmayiarun

The government of India has proposed a draft data protection bill with serious implications for technology and digital services companies that do business in the country. The bill has already generated controversy, with U.S., British, and Indian industry associations writing to the Indian Minister of Electronics and IT. Much of their concern stems from the fact that the new law may require firms to store copies of personal data in India. The law will not only affect technology giants like Facebook, but also companies who happen to have their employee benefits processed in India.

More on:

India has attempted to create a complex new legal framework for data protection in a much shorter period than it took Europe to craft the General Data Protection Regulation. This means that shortcomings are inevitable and implementation challenges are to be expected. Nevertheless, three serious flaws plague the current draft: data localization, law enforcement access to data, and weak oversight.

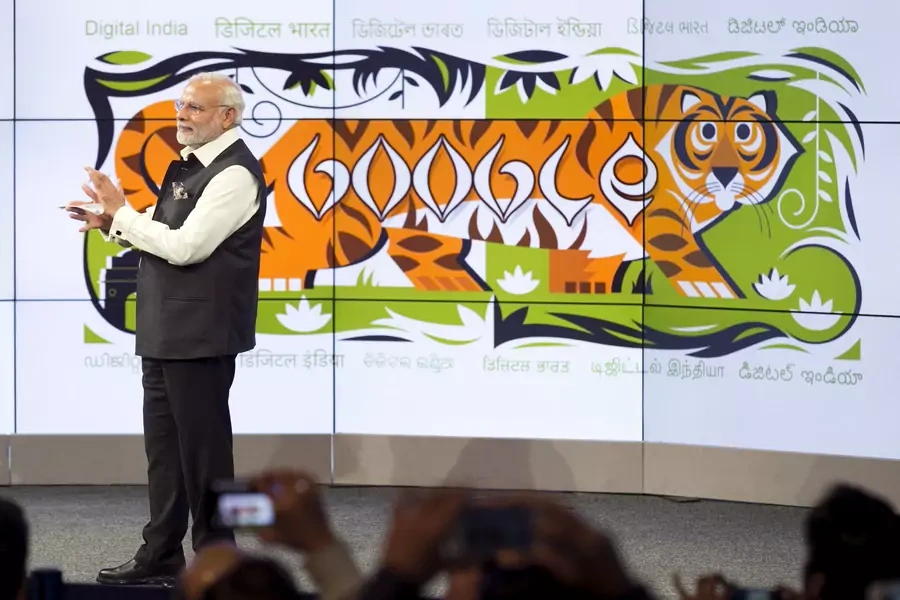

The data localization section of the new privacy bill might be the most prominently controversial element of the legislation. The bill requires data fiduciaries to store “at least one serving copy” of personal data on a server or data center located in India. The government can exempt certain categories of personal data from this requirement. It can also declare certain categories of data “critical” and require that they be stored only in India. In other words, foreign internet intermediaries and services, such as Facebook, Uber, Google, Twitter, AirBnB, Telegram, WhatsApp, and Signal may all be required to physically host user data in India. The only discernible reason for such a requirement is to give law enforcement easy access to this data.

This leads to the second problem with the bill: it allows the processing of personal data in the interests of the security of the state if authorized and according to procedure established by law. In addition, it permits processing of personal data for prevention, detection, investigation and prosecution of any offence or any other contravention of law. This access to all personal data by the state poses an enormous threat to the right to privacy given the weak safeguards that exist in India against state surveillance. In combination with the data localization requirement, the Indian government will have unprecedented access to information about Facebook users.

The legal framework for government surveillance in India continues to be governed by the PUCL v. Union of India framework which was intended as a stopgap measure by the Supreme Court in 1996, but seems to have been adopted permanently. These rules concentrate the power to order and review surveillance in the hands of the executive, without introducing court orders, any form of third party review, or any requirement to notify the subject of surveillance. They fall short of all international human rights standards for acceptable safeguards for state surveillance. Under the circumstances, there will be little to prevent the government from helping itself to the detailed datasets collected about citizens.

Lastly, the draft bill creates a regulatory structure that is not sufficiently independent: the central government has significant control over the regulatory regime, and it is vulnerable to capture by industry. The draft bill gives the central government the power to appoint members of the data protection authority upon the recommendation of an outside committee. The appointment is for a term of five years, which seems much too short to give a new institution sufficient time to learn the ropes and gain the independence it needs to be an effective regulator. The central government also has the ability to remove members of the authority for reasons specified in the law.

More on:

The bill does contain a two-year cooling off period in which members of the authority cannot accept appointments with the government or major data intermediaries. The purpose of this is to avoid regulatory capture, but it is likely to be insufficient. The bill requires that the members of the authority have “specialized knowledge of, and not less than ten years professional experience in the field of data protection, information technology, data management, data science, data security, cyber and internet laws, and related subjects.” India has such a small pool of experts that fit that description that a revolving door will likely be established between the regulator and data fiduciaries being regulated.

Although the data protection bill is not a bad effort given how little time drafters had to produce it, the legislation is far from ready for enactment. The government might do well to consider its own internal drafts, some of which did a superior job of avoiding the various privacy risks that the new data protection bill creates.

Online Store

Online Store