More on:

This post is part of a series on the Indian elections.

In the grand tradition of Jon Stewart, the British comedian John Oliver has skewered American television’s priorities in his new show, Last Week Tonight. His acerbic eight minute bit on the Indian elections—elections historic in scale, with an electorate of 815 million voters and big issues at stake—gets many things right, most importantly, U.S. television’s focus everywhere else. (And even, hilariously, the sad fact of a Fox News segment last week covering not, say, the April 17 fifth phase of India’s elections in which 195 million people went to vote, but instead a ludicrous feature about a leopard on the loose causing panic in India).

I’d like to note first that U.S. print news and their web properties are doing a terrific job covering the largest election in world history as it stretches across its five-week, nine-phase operation. The New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal and Los Angeles Times, have been covering important moments across the country as various states cast their votes, and the additional content offered through the Times’ IndiaInk blog and the Journal’s India Real Time blog are fabulous. Both include a wide variety of dispatches from their correspondents and contributors.

And let me not overlook the always-thoughtful Charlie Rose, who devoted half a program—all talk, all substance—to a stellar panel previewing the Indian elections at the end of March. But I’m hard pressed to find any other sustained focus on U.S. television, on any channel, over the past several weeks. Charlie Rose’s discussion stands in sharp contrast to the litany of errors contained in the McLaughlin Group segment ridiculed by Oliver (in which McLaughlin asks why the Indian elections should concern us, since “they’re not even in our hemisphere”).

Of course, when the national elections kicked off on April 7 there were short spots on many channels highlighting that news, but just as Oliver said, not that much afterwards. While I can imagine it might be hard to devote substantial focus to India on an ongoing basis over a five-week period, the limited attention to India particularly in comparison to coverage of Ukraine or flight MH370 does seem striking.

What Oliver captures is the larger problem situating India within U.S. global attention. Americans tend to look to the immediate south (Mexico), or to Europe and the Middle East, when we think about the world. And when Americans think about Asia, that has more typically connoted East Asia due to our longer history with China, Japan, Korea, and Southeast Asia. This stands in sharp contrast to the British connotation of “Asia,” in which the entirety of the Indian subcontinent features equally prominently.

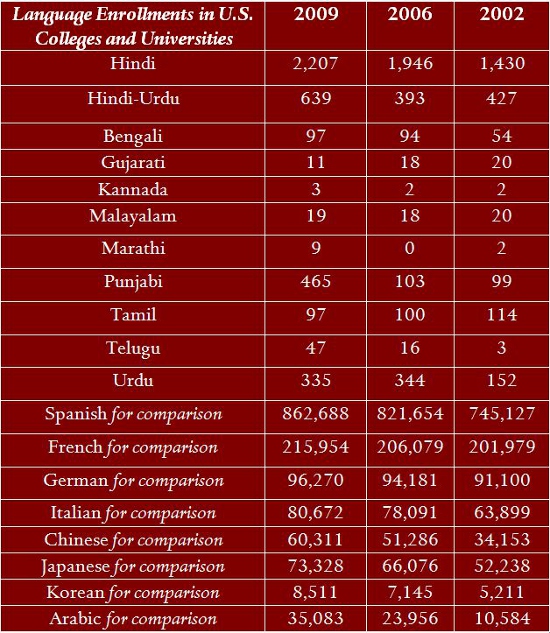

We see this emphasis reflected in patterns of language study in the United States as well, as helpful a metric as any since the data can be measured over time and in comparison to other languages. Even despite increases in the study of Indian languages in the United States over the course of the past decade, the numbers are still small compared with more commonly studied languages, including Asian languages:

The above table provides the most comprehensive data available, but it can be summarized by saying that the total enrollments in all Indian languages combined (3,929 in 2009) account for less than half those of Korean, and a mere fraction of more commonly taught languages (6.5% of Chinese, 1.8% of French, and just 0.46% of Spanish). What we’re familiar with shapes what we pay attention to, naturally.

This is all to say that we’ve still got some work to do in the United States in making the world’s largest democracy more front and center in our discussions about global affairs, a larger part of what we study, and a much greater part of our media coverage. As India’s elections move into their final phases, with results announced on May 16, there’s still two weeks to get this right.

Follow me on Twitter: @AyresAlyssa

More on:

Online Store

Online Store