Strengthening Strategic Technology Cooperation Between South Korea and the United States

Introduction

Technology is central to today’s geopolitical competition. Over the coming decade, critical and emerging technologies will overhaul economies, revolutionize military capabilities, and reshape the world. The form of warfare is changing with the employment of artificial intelligence (AI), unmanned aerial vehicles (drones), robotics, and the increased primacy of cyberspace in military affairs. As emerging technologies pose novel threats, they prompt a new security agenda concerning semiconductor supply chains, 5G/6G technologies, and cybersecurity. Geopolitical dynamics are also changing with intensifying U.S.-China rivalry and global strategic competition in critical and emerging technologies. Those trends accompany new and shared challenges that call for a reconsideration of the scope and nature of partnership between the United States and the Republic of Korea (ROK).

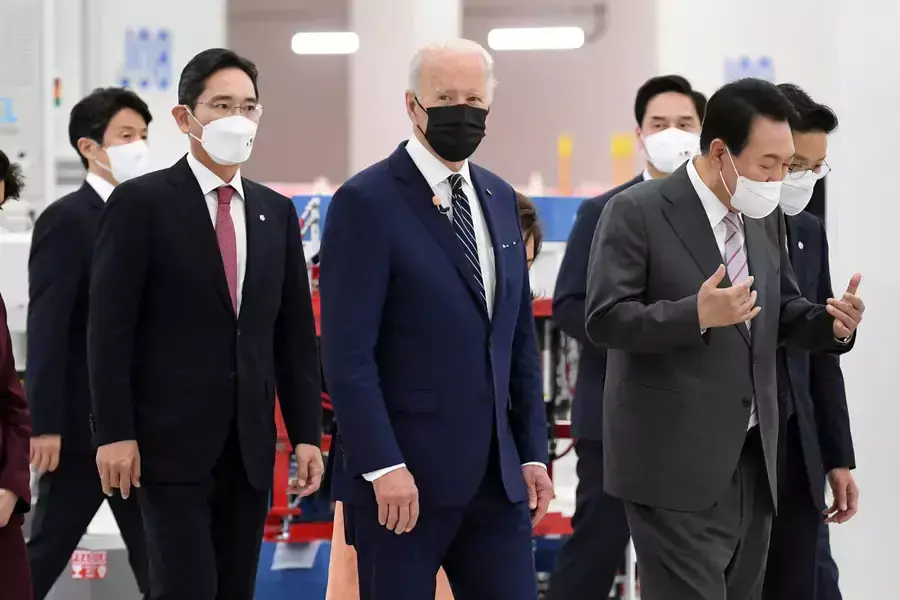

The ROK-U.S. alliance has sustained for more than seventy years based on common vision, values, and purpose. This military-security mechanism has served as an effective deterrent against North Korean attack and contributed to the peace and stability of the region. In May 2022, the joint statement of the summit between ROK President Yoon Suk Yeol and U.S. President Joe Biden proclaimed the upgrade of the alliance to a “Global Comprehensive Strategic Alliance,” which includes a strategic economic and technological partnership.

More on:

The United States also invited South Korea to join the Chip 4 Alliance—an alliance proposed by the United States to invite Asian semiconductor powers such as Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan to counter China’s emerging chip industry—to restructure the semiconductor supply chain and complete the trusted value chain against China. The evolution of the ROK-U.S. alliance into a global comprehensive strategic partnership, with expanded scope to include economic security and advanced technology, signals a more nuanced and forward-looking relationship for the future.

This new development, however, prompts the question of how the two countries can align their needs and opportunities to strengthen their partnership beyond the domain of military security. Additionally, it raises an inquiry into the feasibility and desirability of applying a security logic to technological cooperation. Whether the pace and dynamics of the ROK-U.S. alliance can be adapted to the new environment—in which economic security and technological disruptions intertwine with existing geostrategic challenges—is unclear. As previously noted, the “sustainability of the alliance will depend…on convergent economic interests that enable deeper integration of supply chains and technology.” A greater analysis of the ROK-U.S. alliance sheds light on the desirable form of technology cooperation between South Korea and the United States.

Summary of the CFR Workshop

The Council on Foreign Relations held a virtual workshop on November 1, 2023, on “U.S.-South Korea Policy Coordination Toward China on Technology.” The workshop’s major takeaways include the following:

- Alliances endure when they are founded upon common interests and objectives, credibility in commitments, equity in benefits and costs of the alliance, and strong domestic support. The task for the U.S.-Korea strategic economic and technology partnership is to formulate a common vision overcoming disparities in threat perceptions and dramatic changes in interests within the alliance. The challenge lies in effective communication, not only between the United States and its allies, but also between the Korean government and the public. Clear communication about U.S. rationales and objectives for China-related tech restrictions, assurance of economic security, and mutually beneficial strategies should expand beyond government-to-government dialogues to rally the support of domestic and international audiences.

- In the economic context, private sector competition should be balanced with broad public-private cooperation within the alliance. A framework beyond the government-led focus on technology should engage private sector actors and semiconductor businesses in conversations on cutting-edge technologies. The United States needs to engage in open dialogue with industry leaders, policymakers, and scholars through multi-track diplomacy. This includes parliamentary diplomacy, Track 1.5 meetings, think-tank talks, and various policy discussions.

- Korea’s main strategic consideration is to reduce its risk exposure. Derisking means not only diversifying trade partners or supply chains, but also enhancing ties with other countries that share concerns about China’s influence and actions. Strengthening bilateral and multilateral alliances can provide Korea support in addressing common challenges, reduce Korea’s vulnerability, give opportunities for competitive advantage, and provide a contingency plan for various scenarios such as trade disruptions or political tension.

- The SWOT analysis shows that cooperation between the United States and South Korea should focus on further strengthening South Korea’s global competitiveness and reducing South Korea’s dependence on imports and the Chinese market. The United States and South Korea should discuss how to build collective resilience to counter potential retaliation from China. The Chip 4 alliance has not yet developed to the level of conventional collective security, in which an attack on one country is regarded as an attack on all. Cooperation in emerging and critical technologies and supply-chain networks needs different dynamics and better institutionalization than the existing military alliance.

Tenets of Enduring Alliances

The political scientist Stephen Walt’s work on the collapse and endurance of alliances pinpoints some important tenets of enduring alliances, such as common interests and goals, dependability and credibility in commitments, equity in benefits and costs of the alliance, and strong domestic support. Alliances are more likely to endure when they serve the common interests and objectives of participating countries, preferably when they are founded on ideological affinity and shared values. States need to have confidence that their allies will honor their commitments, especially regarding mutual defense and the alliance’s broader goals. Additionally, states need to feel a sense of fairness in cooperation through equitable burden-sharing and sufficient rewards. Leaders need strong domestic backing for the alliance because domestic opposition or public disillusionment can pressure leaders to reconsider their commitments.

More on:

This framework can be applied to the new ROK-U.S. global comprehensive strategic alliance that extends to the economic and technological security arenas. While the ROK-U.S. alliance has continuously evolved, it is now confronting the securitization of supply chains and technology ecosystems as technology nationalism grows around the world. Some essential components of an enduring alliance—common objectives, credibility in commitment, and dependability—are put to the test in the current geostrategic environment.

Threat Perception and Credibility in Commitment

The United States portrays the nature of competition as one between democracies and autocracies, in which key democratic partners should work together to protect the rule-based international system. China is considered a competitor intending to expand its sphere of influence in the Indo-Pacific region and to reshape the international order with its economic, diplomatic, military, and technological capabilities. There are specific concerns that China possesses the advanced technological capacity to pursue those objectives, and that it could try to exert influence over global technology standards and practices in a manner that favors its own interests and values. Against this backdrop, the U.S. national security strategy’s top priority is maintaining a competitive edge over China in technology and economics. The United States perceives China’s rapid state-driven innovation in critical technological sectors—potentially even surpassing the United States in emerging areas such as AI and quantum computing—as a threat to the United States’ technological and global competitiveness. The November 2022 U.S. national security strategy paper affirms that “the US, in close coordination with the allies and partners, will establish fair rules while also sustaining its economic and technological edge and shape a future defined by fair competition,” linking the problem of insecure supply chains to the abuses of China’s nonmarket economic actions.

The U.S. security logic for countering Chinese technology threats, however, fails to articulate specific goals, trade-offs, or justifications for decoupling with China. There are many distinct policy rationales for the U.S. government’s new technology controls aimed at China, including the desire to reduce national security threats, facilitate economic gains, and achieve other collateral purposes unrelated to technology. The potential policy aims are equally diverse, and entail maintaining a military edge over China, limiting Chinese national security espionage, preventing Chinese sabotage in a crisis, limiting Chinese influence operations, countering unfair Chinese economic practices and intellectual property (IP) theft, competing and leading in strategic industries, obtaining general leverage over China, and shaping U.S. domestic narratives.

South Korea shares U.S. concerns regarding China’s misuse of technologies, yet it does not view China as an imminent national security threat. China stands as South Korea’s largest trading partner and a significant market for Korean manufacturers. Picking a side in U.S.-China tech competition and supply-chain crises poses grave economic and diplomatic challenges for South Korea. Until the previous government, South Korea pursued a balanced and open stance to retain Seoul’s trade relationship with Beijing and security alliance with Washington. The Yoon government shifted foreign policies to align more closely with the United States and Japan, prioritizing the U.S.-South Korea alliance and Indo-Pacific strategy. However, domestic discontent over the economic consequences of this strategic choice is currently holding back President Yoon’s ambitious foreign policy. Joining regional partners to coordinate export controls, decoupling policies, or reshoring manufacturing capacity from China will be a substantial risk to the Korean economy. There is no assurance that a robust economic alliance with the United States based on increased security collaboration will offset South Korean losses in the Chinese market.

South Korea’s position with respect to China remains unclear, as South Korea wishes to maintain a mutually respectful relationship. The South Korean government will choose to de-risk rather than decouple with China to find a better balance between national security and economic interests. U.S. political discourse that overinflates Chinese technology threats or value-based diplomacy without a unified objective and strategic clarity is insufficient to bolster the dependability of the United States or merit a full commitment from technologically advanced partners such as South Korea.

Domestic Support

South Korea’s commitment to technology cooperation with the United States, particularly in the context of the Chip 4 alliance, is challenged by a polarized and complex domestic political environment. The “blatant protectionism and unilateralism” exhibited by the U.S. CHIPS and Science Act and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 was condemned by Koreans, who saw those policies as using the rhetoric of international norms and securing supply chains to serve U.S. economic interests. While the United States emphasizes national security as its rationale for restricting Chinese access to advanced chip technology, the CHIPS and Science Act and IRA appear to be driven more by U.S. commercial interests, with the intent to restructure the Asia-concentrated semiconductor supply chain to be centered on the United States. A Dong-A Ilbo public poll showed that 77 percent of Koreans see the CHIPS and Science Act as an America-First policy and 82.6 percent of Koreans think the United States should consider its allies’ benefits.

Public opinion shows a clear polarization on the economic and security interests of Korea vis-à-vis the intensifying U.S.-China rivalry. According to a 2023 Hankook Ilbo poll of the Korean public, 63.2 percent of Korean respondents agreed “Korea should not tolerate economic losses in the semiconductor industry even if it can cause problems for the ROK-US alliance.” At the same time, more Korean respondents considered security cooperation with the United States as more valuable than economic or industrial cooperation. A Korea Chamber of Commerce and Industry survey of Korean semiconductor experts showed a corresponding pattern: 46.7 percent of the experts replied that Chip 4 would negatively impact the domestic semiconductor industry, while 36.6 percent viewed the impact to be positive. Nevertheless, most experts (92.3 percent) agreed that China would not be the best partner for tech cooperation and expressed concerns about technology leakage to China. A public poll conducted by the Asan Institute for Policy Studies showed a similar result when asked which country South Korea should strengthen ties with if the United States and China continued their rivalry. More than 80 percent of South Koreans preferred the United States as a prospective partner.

President Yoon’s approval rating, which is hovering around 30 percent, is another significant challenge to a potential ROK-U.S. tech partnership. While there is generally bipartisan support for the alliance in the U.S. Congress, South Korea exhibits stronger conservative-leaning support. If this level of disapproval contributes to the outcome of the 2024 general election, it could undermine President Yoon’s vision to forge a comprehensive strategic alliance with the United States or continue pursuing its Indo-Pacific strategy. Furthermore, South Korea is concerned about the prospects of the next U.S. presidential election and the possible resurgence of America-First rhetoric with a change of administration. Such a shift could lead to alterations in South Korea’s national security strategies and global outlook, adding uncertainty to the global comprehensive strategic alliance.

Economic Security: Equity and Benefits

The intensifying competition for economic interests, the weaponization of industries and resources, and the fragmentation of global supply chains are increasingly endangering the domain of economic security. Economic security, by definition, is “a state in which national security is maintained and economic activities are unhindered by ensuring the smooth inflow of essential items of the nation’s economic activities and preventing inappropriate outflow, regardless of domestic and international variables.” In the context of U.S.-China competition, the term “economic security” has gained prominence with the rise of tech alliances and the reconfiguration of high-tech supply chains. Korea’s economic-security dilemma revolves around how to maximize the benefits and minimize the risks of cooperation with the United States. Conducting a SWOT analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) offers a comprehensive assessment of the potential opportunities, challenges, and strategic considerations for South Korea.

South Korea’s global competitiveness derives from its technological competency and talented workforce. Korea has leading businesses in the semiconductor sector with high competency in memory-conductor production and micro-process technology; its invitation to the Chip 4 alliance comes from such strengths. Its main weakness is its high dependence on imports for materials and equipment: 90 percent of semiconductor raw materials are imported from the United States, China, and Japan, and more than 77.5 percent of equipment is from the United States, Japan, and the Netherlands, in which 24 percent of materials and equipment comes from China. The significant investment and heavy dependence on China’s market, as shown by the on-site foundries of Samsung and SK Hynix, are a liability rather than an asset for Korea amid supply-chain reconfigurations.

Tech collaboration with the United States offers opportunities for South Korea. First, Korea could join an alternative regional economic bloc that guarantees a transparent environment for innovation and competition, and a more stable and resilient global supply chain centered on allies and like-minded states. The proposed Chip 4 alliance acts as a viable platform for the United States, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan—who jointly control 78 percent of the global semiconductor supply—to collaborate on innovating advanced semiconductors and other critical technologies. This would enable Korea to reduce its dependence on China, safeguard against Chinese economic coercion, and leverage a competitive edge while benefiting from the U.S. containment strategy against China. Korea could also enjoy the expansion of the U.S. semiconductor market share by establishing foundries in the United States. Second, Korea could participate in the process of setting international technical standards and outcompete hostile states on certain critical technologies. The United States proposed the National Standard Strategy for Critical and Emerging Technology (CETs), and stressed close cooperation and partnership with its allies in technological areas. Proactively engaging with the United States in the discussion to form and implement international rules and standards for CETs from the early stages could enhance Korea’s technological competitiveness and economic security while yielding favorable conditions for its mid- to long-term innovation strategies and reducing transitional costs.

Conversely, there are also threats associated with friendshoring, decoupling, and export control. China is Korea’s biggest trade partner and a hub for Korea’s main overseas semiconductor manufacturing facilities. Decoupling with the Chinese market, an important source of raw materials and a market for semiconductor companies, could be committing commercial suicide. Friendshoring and reshoring would likely trigger immediate economic losses. China’s possible retaliation through export or import control and economic coercion could further damage South Korea’s economic security. Of all the nations invited to the Chip 4 alliance, Korea is the most vulnerable, as Korea exports 60 percent of its semiconductors to China (including Hong Kong) and imports more than 75 percent of essential raw materials from China. This contrasts with Taiwan and Japan, which are much less dependent on China, with less than 10 percent and 30 percent of imports respectively. Another potential risk is the heightened dependence on the United States, which could limit the growth of South Korea’s CET and chip industry. The United States is seeking to establish a semiconductor ecosystem within its borders by encouraging its allies to increase their share of semiconductors produced in the United States at their own expense. Those measures put immense pressure on South Korean chip manufacturers and raise doubts about whether the United States intends sincere cooperation with its allies or a gradual assimilation of their industrial capabilities. Given the uncertainty surrounding dependability, Korea will likely adopt a more assertive stance in securing technological sovereignty and diversifying its partners to reduce dependence on any single country.

The SWOT analysis illustrates that siding with the United States could be costly and risky for Korea’s economic security. The demerits of joining the tech alliance and friendshoring are apparent, especially for Korean semiconductor manufacturers active in China. Tech companies and enterprises compete for profit and innovation while considering tradeoffs. The private sector appears reluctant to forge long-term multilateral collaboration on semiconductors apart from participating in the fundamental research phase. The national security logic cannot override the principle of “free and fair trade” in the economic sector. However, siding with the United States could yield opportunities such as new markets, stable supply chains, and a greater say in setting standards for CETs, which could help maximize Korea’s economic and strategic interests in the long run. U.S. funding could boost Korean businesses via tax exemption and subsidies, expedite technological progress, and enable Korea to secure a stable global semiconductor chain. Regrouping and regaining technological momentum can be a time-consuming process. As the transformations promised by AI are still in their early years, patience and trust between all parties are necessary to ensure dependability and equity in benefits in the new era of U.S.-China competition.

Implications for the Tech Alliance

A new paradigm of cooperation between South Korea and the United States—such as the Chip 4 alliance or the ROK-U.S. tech alliance—could be desirable, but does not appear feasible considering the complexities of balancing security and economic interests. The potential members to Chip 4 are divided as to the urgency and extent of China’s threat, disparities in national capabilities, and varying levels of security and technology integration. This contrast is particularly pronounced in the realm of semiconductors. While the United States regards these prized chips as a matter of national security, South Korea predominantly views them as an economic concern. The competitive nature of the semiconductor industry, coupled with its vulnerability to geopolitical disruptions in global supply chains, poses a potential obstacle to realizing the objectives of the tech alliance. Without a shared vision and cohesive policy frameworks encompassing both offensive and defensive strategies, it is difficult to anticipate a unified commitment from partner countries.

A lack of credibility in the U.S. security logic placed on decoupling, friendshoring, and actions vouching for commercial interests could harm cooperation. Guided by the concept of economic security, the Biden administration has adopted an industrial policy that channels significant public investment at improving the U.S. domestic economy while enhancing its competitive edge against China and other autocratic regimes. In doing so, the administration has constructed a narrative that embraces U.S. allies and partners as upholding democratic values. However, targeted U.S. export controls on semiconductors, national security guardrails connected to U.S. subsidies, and U.S. efforts to form various multinational groups around the concept of economic security have resulted in misunderstandings and risks for its allies. Without a shared understanding of economic security and the divergent interests of its members, it will be difficult to find a mutually beneficial strategy that can incentivize the Chip 4 alliance.

Recommendations

Alliances endure when they are founded upon common interests and objectives, dependability and credibility in commitments, equity in benefits and costs, and strong domestic support. The same tenets apply to the ROK-U.S. global comprehensive strategic alliance. As South Korea and the United States continue to adjust their foreign policies and security outlooks in the era of geo-technological competition, the importance of supply-chain resiliency and critical technologies will gain further momentum. Greater technical and policy coordination between the two countries is vital to cement an enduring ROK-U.S. alliance. Drawing from the conclusions reached in policy dialogues among experts from the United States and South Korea, here are some proposed recommendations:

- To bring technologically advanced partners on board to the U.S. side, a mixture of inducement, pressure, and persuasion based on an agreed purpose and strategy for technological decoupling will be needed. The United States should recognize the diverging interests of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan and their constituent semiconductor industry partners to protect and champion their own semiconductor companies within the new structure.

- To safeguard hegemony in standard-making based on economic and tech cooperation with its allies, Washington should work with technologically advanced allies and global stakeholders to create a shared policy framework. The United States should consult more closely with its allies and partners in the policymaking process to create integrity and inclusivity in the standards system that can ensure sustainability and dependability.

- To strengthen science and critical technological partnerships, the United States and South Korea should cooperate in sharing information, promoting investment, and establishing common standards for CETs in the areas of AI, robotics, 5G/6G networks, and cyberspace. Collaborative efforts in technology between the United States and South Korea should prioritize low-risk, easily achievable initiatives. Those include joint research and development (R&D); the establishment of a shared R&D funding pool; the exchange of science, technology, education and math (STEM) talents; the adoption of shared standards and regulatory frameworks; and the implementation of joint cybersecurity measures in line with the Strategic Cybersecurity Cooperation Framework.

- To gain stronger domestic support for forging a new tech alliance with the United States and its Indo-Pacific strategy, the Korean government should emphasize safeguarding national security and economic interests and mitigating any potential risks to relevant industries. Both countries should improve coordination and communication through multi-track diplomacy to reduce political backlash from the public.

Conclusion

The technology competition between the United States and China is essentially about who will set the rules in the new domain of security and economy. Emerging technologies and technological innovation are viewed as strategic assets and game-changers in the competition for influence and hegemony in the future. The United States will need the support of its allies and partners to increase its competitive edge in a range of advanced technologies. South Korea will also need the United States and other partners to enhance its competence through participating in the restructuring process of the semiconductor supply chain and rule-setting in the CETs connected to its main industries. This can be an opportunity for mutual synergy to meet the common objective of strengthening the new order in the technological ecosystem. Although the comprehensive strategic alliance is far more complicated and requires complex preconditions for such arrangements to transpire, this new technology partnership beyond the asymmetric military-security relationship is critical to reinforce the ROK-U.S. alliance for decades to come.

Soyoung Kwon is associate professor of global affairs and director of security policy studies-Korea of the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University.

Online Store

Online Store