Nepal: Back on the Political Track

More on:

There have been a lot of elections in South Asia in recent days. On November 16 a run-off election produced a surprise result in Maldives, where Abdulla Yameen—the half-brother of former President Gayoom—narrowly succeeded over Mohamed Nasheed, who had led the previous two first-round elections. The Indian state of Chhattisgarh (the size of a small country, with about 25 million people) had its first phase of state-level polls on November 11. And on Tuesday, November 19, there will be two elections underway in the region—the second phase in India’s Chhattisgarh, as well as the long-overdue national Constituent Assembly elections in Nepal. India will count the results from five different state elections on December 8, so we’ll all have to wait to find out who wins.

Nepal’s elections mark an opportunity for the country to get back to business politically. This country of 30 million people has been without elected representatives since the expiration of the last Constituent Assembly on May 27, 2012. The Assembly, comprised of 601 representatives, was created in April 2008 initially as a two-year body at the end of Nepal’s long decade of internal conflict, tasked with seeing through the peace process and drafting a new constitution for a country that has moved from monarchy to constitutional monarchy to insurgency to democracy. On management of the peace process, the former Assembly did quite well. Nepal has successfully dealt with the enormously difficult post-conflict question of how to demobilize former combatants, integrating some into the Nepali Army, and helping others move into retirement or new livelihoods. Many countries would do well by learning from Nepal’s experience here.

But it was the constitution drafting exercise where the former Assembly foundered. Despite four extensions, in the end members could not reach agreement on federalism-related issues (like the number of provinces, on what basis they might be formed, what they would be named, among others) and the Assembly lapsed. Since then, Nepal has been in an interim state of government—not a crisis, but not proactively advancing the important developmental agenda that its citizens want. For a country long held out as one of great hydropower and tourism potential (but a potential unrealized), the ongoing political instability has not facilitated needed investment, to quote the head of the Non-Resident Nepali association.

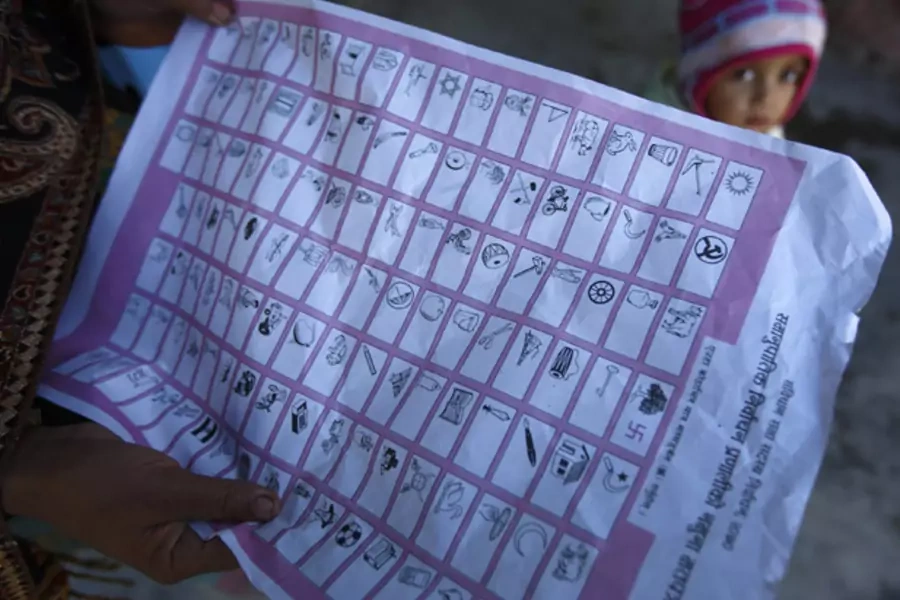

Current press coverage has focused on voter disappointment “by the bickering among parties and a flailing economy,” with the “euphoria” of the 2008 national elections decidedly missing. There does not appear to be a clear front runner, and with more than 120 parties registered, “fractured” best describes the electorate. The party with the single largest number of seats in the previous Assembly, the Unified Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist), headed by Pushpa Kamal Dahal (known for years by his nom de guerre, Prachanda), is seen as vying for votes with the Nepali Congress, headed by Sushil Koirala, in part due to a split in the Maoists. But there are so many smaller parties, and the general consensus is that no single party will have a definitive victory, so coalition formation will be the important thing to watch.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store