Latin America’s Middle Class

More on:

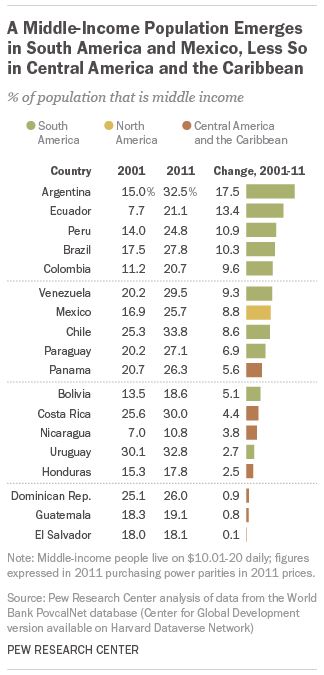

The first decade of the 21st century was a good one for Latin America. A recent Pew Research Center report estimates that some 63 million individuals entered the middle class, measured as earning between ten and twenty dollars a day. Add in the 36 million more members of the upper-middle class, and 47 percent of those in South America—a near majority—are no longer poor. Mexico brought over 10 million people into its middle ranks during the decade, raising the combined share of the middle and upper classes to roughly 38 percent of the population.

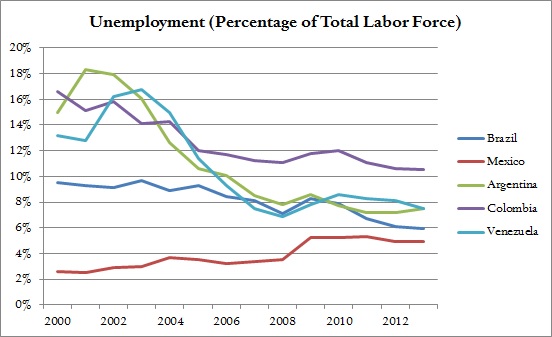

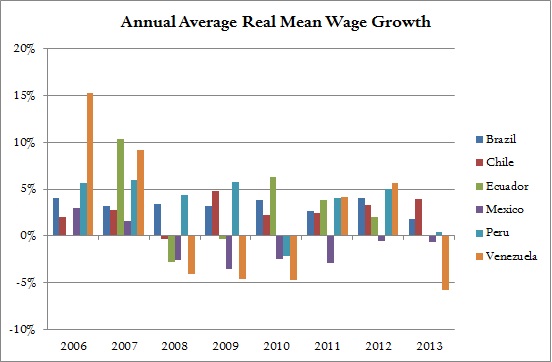

Unsurprisingly, the commodity boom helped. Demand for oil, soybeans, copper, iron ores, and numerous other raw materials boosted investment, increased exports, and created jobs. Abundant global capital and easy credit spurred public and private consumption, lifting consumption of the middle even more, and supporting expanding retail sectors and employment. Government policies, in particular conditional cash transfer programs such as Oportunidades in Mexico and Bolsa Familia in Brazil reduced inequality and poverty as well. With historically low unemployment rates and rising real wages, the middle thrived.

Slowing growth since 2013 is now reversing some of these gains. With Brazil, Argentina, and Venezuela already in recession, the IMF projects regional growth of just half a percent for 2015. Falling commodity prices and higher public and consumer debt levels mean exports and consumption are down. As nations search for new growth engines, weak schools, bad infrastructure, and limited R&D investment leave them with few easy short-term options. Governments too are limited in their ability to fill the gaps, given increased debt loads and relatively weak tax collection.

The report is somewhat pessimistic about the prospects for this newly emerging middle class. Many live paycheck to paycheck, and are deeply indebted. In Brazil, average household debt—mostly high interest consumer credit—now stands at 46 percent of disposable income. One study estimates that 14 percent will fall back into poverty in the coming decade.

The prognosis is not all bleak. Central America, which missed the earlier uptick, could see its middle class grow. And recent data from Mexico shows poverty continuing to decline in many of its northern states (even as it rose overall).

Interestingly, the positive results in many Mexican states and hopes for Central America’s middle ranks depend on U.S. trade ties. The United States remains the world’s largest consumer market, its draw heightened as China falters and the EU stagnates. And U.S.-Latin America exchanges are more likely to rely on manufactured goods and services than raw materials, another benefit as these nations work to protect and expand their middle income sectors. Whether countries are able or not to expand these ties, the coming decade will prove much harder for the region, both for those that gained and those that did not, during the boom.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store