How Not To Estimate and Communicate Risks

More on:

Estimating and translating the probability of an event for decision-makers is among the most difficult challenges in government and the private sector. The person making the estimate must be able to categorize or quantify a likelihood, and willing to relay that analysis to the decision-maker in a way that is comprehensible and timely. The decision-maker then must consider the probability within the context of other information, and subsequently consider the trade-offs between one course of action over another. The ultimate goal of perceiving and communicating risks is to best assure any institution has managed those risks and made the most sound choice possible in the time allotted.

There were fascinating paragraphs hidden in a recent NASA Office of Inspector General (OIG) report—NASA’s Response to SpaceX’s June 2015 Launch Failure: Impacts on Commercial Resupply of the International Space Station—about the inherent challenges that come with estimating probabilities. On June 28, 2015, a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket carrying a cargo resupply mission to the International Space Station (ISS) failed two minutes after liftoff. The rocket along with a capsule and $118 million worth of NASA cargo it was carrying was destroyed. SpaceX later determined through recovering parts of the Falcon 9 and telemetry analysis that the likely cause was a “strut assembly failure” during the rocket’s second stage.

The June 2015 event had been the second commercial resupply mission failure in eight months, following a failed liftoff of an Orbital ATK’s third mission (termed, Orb-3). Given that SpaceX and Orbital are the only two commercial space providers to have successfully supplied the ISS—a third, Sierra Nevada Corporation, was awarded resupply contracts, but has not launched yet—the OIG examined NASA’s response to the SpaceX failure and its efforts to reduce the risks associated with future missions.

On pages twenty and twenty-one of the report, the OIG reveals that “there is no integrated presentation or package that documents all risk areas for a given launch. Instead, separate presentations are used to determine the ‘acceptable’ risk posture—a term that evolves frequently.” The report then contains the following passage:

Although the flexibility in determining and altering the nature of an acceptable risk posture has some benefits, it may also introduce confusion into the process. For example, senior NASA officials have stated that high levels of risk for cargo missions are tolerable, noting the expected risk of mission failure for a typical [Commercial Resupply Services] launch is one in six. However, as stated in the Orb-3 Independent Review Team’s report, NASA engineering personnel expressed significant concerns about the Orb-3 launch vehicle’s engines and the recent failures Orbital had experienced on test stands, characterizing the likelihood of mission failure for Orb-3 as "50/50." In contrast, the ISS Program’s risk matrix reflected the risk of Orb-3 engine issues as "low" and assigned a subjective risk of "elevated but acceptable."

Although according to some ISS Program officials NASA management is generally willing to accept heightened risk for cargo missions, it is unclear whether senior NASA management clearly understood the increased likelihood of failure for the Orb-3 mission. Even so, the disparity between 50/50 and one in six for the same mission raises questions about the adequacy of communication between the engineers and top program management [emphasis added].

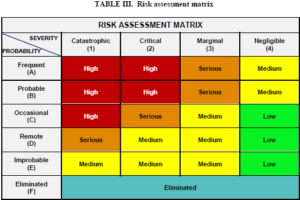

Such estimates are inherently subjective, but nevertheless they captured somebody’s degree of belief of the probability of mission failure. As we know from the work of scholars like Baruch Fischoff and Richard Zeckhauser that combining numerical estimates and probability expressions leads to confusion among decision-makers. Moreover, when people are asked to assign a numerical probability to phrases like “low” or “elevated but acceptable” they will offer a wide range of numbers. To mitigate against such ambiguity, a U.S. Intelligence Community directive assigns percentage ranges for probability expressions. “Unlikely” to “improbable” are 20 to 45 percent, while “very likely” and “highly probable” are 80 to 95 percent. The Department of Defense uses a different method for assessing risks, which is posted below:

Naturally, any decision-maker would react differently, and potentially opt for an alternative choice, to a 17 percent or 50 percent probability—the contrasting “one in six” and “50/50” estimates that were found by the NASA OIG.

In 1964, Sherman Kent, a pioneer in intelligence analysis, published an important piece—“Words of Estimative Probability”—in the CIA’s in-house journal, Studies in Intelligence. Kent reviewed the ambiguous words, phrases, and numbers that analysts have used to translate likely outcomes for policymakers. Kent wrote that “once the community has made up its mind in this matter, it should be able to choose a word or a phrase which quite accurately describes the degree of its certainty; and ideally, exactly this message should get through to the reader.” Apparently, there was no such standard used between the two commercial space providers and the ISS program managers, introducing needless uncertainty upon which decisions were made.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store