Financial de-globalization, illustrated

More on:

The financial world has changed -- even if the scale of the change isn’t obvious in the financial sector’s 2008 bonuses.

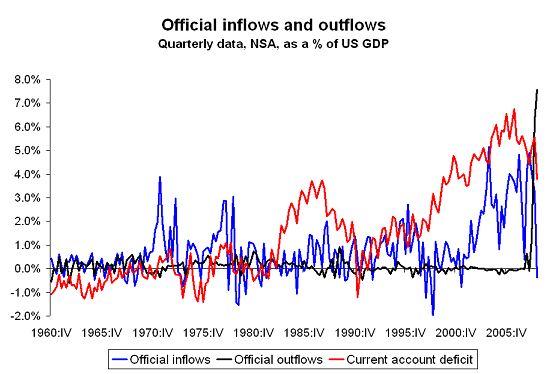

Here is one indication of the scale of the change: the US government was -- according to the latest US balance of payments data -- a large net lender to the world. Yes, a net lender, not a net borrower. Foreign central banks are no longer providing the US with much new credit. Indeed, they withdrew $13.6 billion of credit from the US in the fourth quarter, as central banks’ agency sales ($96b) and the fall in their deposits in US banks (bank CDs fell by $80 billion) produced a net outflow despite record purchases of US treasuries ($179b, all short-term bills). And the US -- through the Fed’s swap lines -- provided a rather large sum of credit ($268 billion) to the rest of the world. For the year as a whole, the BEA data indicates the US government lent $534 billion to the rest of the world while foreign governments lent "only" $421 billion to the US.

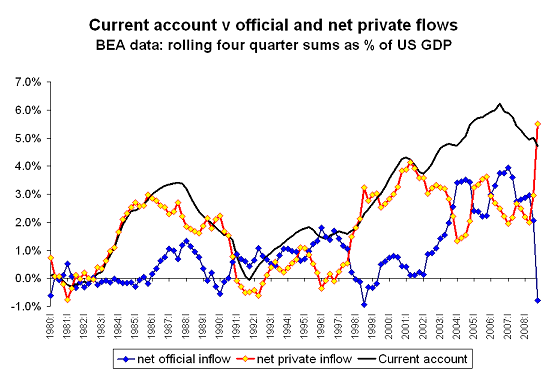

Judging from the data on net flows, Bretton Woods II has in some sense come to an end. The world’s central banks are no longer building up reserves and thus are no longer a net source of financing to the US. It just didn’t end in the way the critics of Bretton Woods II expected -- on this, Dooley and Garber are right. The fall in official flows* was offset by a rise in (net) private inflows.

Then again, Bretton Woods II also didn’t anchor a stable international financial system in the way Dooley and Garber suggested either. Both private and official demand for US financial assets has collapsed. Gross inflows are close to zero.

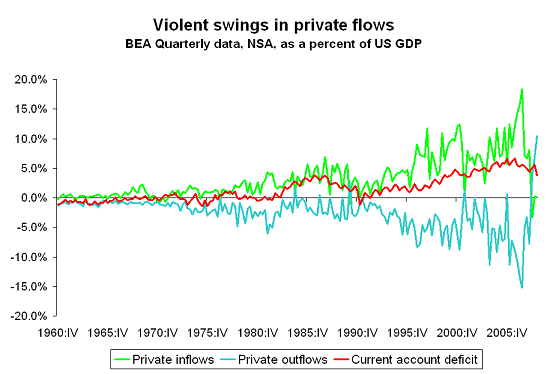

How then can the US still run a large current account deficit if the rest of the world isn’t buying its financial assets? There is only one answer: Americans have pulled funds from the rest of the world (call it deleveraging, call it a reversal of the carry trade or call it a flight to safety) faster than foreigners have pulled funds from the US market. Words cannot really capture the sheer violence of the swings in private capital flows that somehow produced a a rise (net) private demand for US financial assets. The modest change in net flows reflects an enormous contraction in gross flows. Look at the quarterly data -- not a rolling four quarter sum -- scaled to US GDP.**

To put in in plain terms, Lehman’s collapse had a bigger impact on cross-border flows than 9.11. Compare q4 2008 to q3 2001.

The enormous withdraw of private US lending to the world was offset, in part, by a surge in US official lending to the world. It was just the Fed, not the Treasury, that did all the heavy lifting.

For now, Dan Drezner doesn’t need to worry too much about the United States’ ability to be the world’s lender of last resort. A crisis may come when the US government cannot play a similar stabilizing role. But that crisis would be marked by a run out of the dollar -- not a global scramble for dollars. The current crisis has constrained the United States’ ability to be the world’s importer of last resort, but not its ability to be the world’s lender of last resort. Not so long as the the world is scrambling to find dollars, the one currency the Fed can create. Here, my earlier concerns haven’t been born out.

Still, it is hard to look at these charts and conclude all is well in the world. Cross-border financial flows rose to crazy heights during the credit boom. Thank the shadow financial system. Over the past year those flows have collapsed with stunning speed.

Had the collapse in inflows and outflows not offset, there would now be talk of a sudden stop in capital flows to the US. But so long as the fall in demand for US assets is matched by a fall in US demand for foreign assets, a collapse in gross flows need not to lead to a collapse in net inflows. To date, the United States "sudden stop’ has manifest itself as a credit crisis not a currency crisis.

The "great contraction" in private capital flows actually started in the summer of 2007. The pressure that led to Lehman’s failure -- and the near-failure of a host of other financial institutions, not the least AIG -- had been building for a while.

And it is also striking, at least to me, that financial globalization collapsed of its own weight, not because of any political decision to throw sand into its gears. That may yet happen. The political reaction to the financial excesses of the past few years is just beginning. But the fall in financial flows to date largely reflects the unwinding of a a host of leveraged bets made by the City and the Street -- not demands from Whitehall or Washington.

Indeed, without government intervention, the collapse in cross-border flows would have been far larger. If the government hadn’t stepped in, a host of financial institutions would have collapsed, leading to an even sharper contraction in capital flows. That is something that often seems to be lost in the debate over financial protectionism.

The data for the charts can be found here.

* The BEA data understates official flows from mid 2007 to mid 2008, as it hasn’t been revised to reflect the results of the survey data. Even the revised BEA data understates the impact of central banks and sovereign funds as it doesn’t capture those funds that have been handed over to private fund managers, or the purchases of US securities by European banks with a large dollar balance sheet as a result of large central bank deposits. This isn’t an issue for the tail end of 2008 though. The fall off in official demand is real. Central banks were in aggregate selling off there reserves -- as the IMF’s forthcoming COFER data will show.

** A negative outflow is functionally the same as an inflow; a current account deficit can be financed by borrowing from the world (an inflow), selling equity to the world (an inflow) or by reducing your lending to the world (a negative outflow, and since outflows have a negative sign of the balance of payments data, a negative outflow generates a positive flow) and/ or selling your existing stock of foreign investments (a negative outflow).

More on:

Online Store

Online Store