Could the ICC Be Assad’s Way Out?

More on:

Reports emerged on Wednesday that Saif al-Islam, the son of Libya’s former strongman Muammar Qaddafi, is seeking surrender to the ICC. Saif, one of the former regime’s most wanted men, was charged by the ICC with crimes against humanity in June. A source tied to the National Transitional Council reports that Saif “believes handing himself over is the best option for him.”

Following the onset of NATO’s intervention in Libya, while Qaddafi still firmly controlled Tripoli, many, including me, questioned the wisdom of charging the Libyan leader at the ICC at that point in time. It was not that he wasn’t worthy of such an indictment. Rather, the concern was that taking Qaddafi to the ICC before he had stepped down would only make it less likely for him to seek a safe haven abroad. Since the Rome Statute, which established the ICC, entered into force in 2002, 116 countries have become party to it thereby significantly constricting the number of countries to which dictators can flee without fear of prosecution. Thus, ICC indictments could have the unintended consequence of prolonging conflicts by encouraging dictators to hang on since they have fewer places to flee. That still may be true.

But Saif’s reported plea to be taken to the ICC shows the other side of the coin: indictments at The Hague could provide those likely to face certain death at home for their brutal crimes against their own people with a more attractive sanctuary.

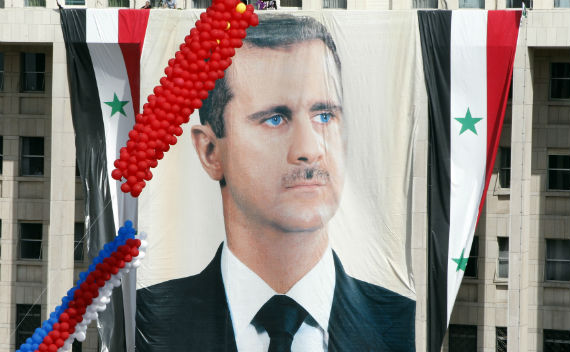

This recent episode in Libya may be worth considering in light of the call by a group of U.S. senators earlier this week for the UN Security Council to charge Syrian president Bashar al-Assad at the ICC with crimes against humanity. Is it possible that as in the reported case of Saif al-Islam, the ICC could provide Bashar al-Assad with an exit strategy—a way out preferable to staying in place?

For the ICC to be a carrot, it seems, the other sticks must be rather large. That is, leaders are likely to seek a one-way ticket to The Hague only after they have lost power and are looking at certain death at the hands of their own people. Otherwise, certain indictment at the ICC is likely to remain more of a disincentive to stepping down. Staying put will look more attractive.

At this point, Bashar al-Assad is certain to gamble on the distinct possibility, if not probability, that he can hold onto power in Damascus. Should the international community seek to induce the Syrian dictator to go into exile while indicting him at the ICC, then the choice of possible havens available will be limited to those countries that have not ratified the Rome Statute.

Having ruthlessly killed more than 3,000 Syrians already, indicting Bashar at The Hague is no doubt morally and legally justified. For it to serve as an incentive for him to step down or modify his behavior, however, charges at the ICC will probably have to be paired with significantly greater pain, if not certain death, to him and his regime.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store