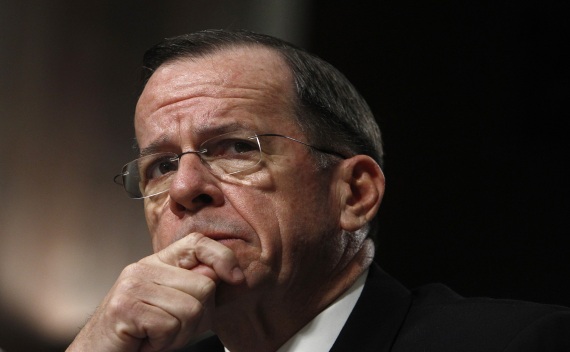

Admiral Michael Mullen: Farewell and Thank You

Tomorrow, the Pentagon will hold a ceremony celebrating the service and retirement of the seventeenth Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Michael Mullen. While he served as chairman during two wars, combined with bi-monthly trips to twist the arms of Pakistan’s military leadership, Mullen should be remembered for his integrity as the nation’s most senior military official, relentless efforts to raise awareness of the mental health problems facing deployed service members, and courage to take positions that put him at odds with many in uniform, including the service chiefs.

The role of the chairman under the Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986—commonly known as Goldwater-Nichols—is straightforward: “The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff is the principal military adviser to the President, the National Security Council, and the Secretary of Defense.” In addition, the chairman offers strategic guidance to the armed services—that should be bureaucratically neutral—and directs the Joint Staff planning for operations. The chairman, however, is not in the chain of command for operations and cannot order troops into battle. As a practical matter, the position’s authority rests in being a conduit for communications between the Pentagon’s senior officials and combatant commanders in the field.

Admiral Mullen’s legacy will center on three issues:

First, he reestablished what he believed was the proper role of the chairman. Under Donald Rumsfeld’s tenure, chairmen found their authority undermined by the secretary of defense. Bob Woodward reported that, “At one point Rumsfeld suggested that [General Hugh] Shelton ought to give his military advice to the president through him.” Shelton, appropriately, said no. In an effort to weaken his influence, Rumsfeld also needlessly tried to gut General Shelton’s support staff of nineteen aides, public affairs officers, speechwriters, and legislative affairs assistants.

The chairmen after General Shelton—Richard Myers and Peter Pace—operated under a highly constrained environment. At the secretary of defense’s request, they would meet with Rumsfeld every day for four to five hours. Woodward even reports that, “Myers found Rumsfeld so hands-on that…he wondered why he was even there.” Rumsfeld claims this was done to solicit their advice, but many other participants recall that it insured that the chairmen did not have independent opinions that could be offered in interagency meetings. Several officials told me that Myers and Pace rarely spoke in White House, unless directly addressed by President Bush.

With Rumsfeld out of the way, Admiral Mullen became the Chairman in October 2007 and immediately set a new tone. Retired Army Gen. Jack Keane told me in a September 2007 interview that he often provided advice to Gens. Pace and David Petraeus, then-Commander of U.S. forces in Iraq. In addition, Keane helped promote the Iraq “Surge” plan, the initial drafts of which were not developed through the normal chain of command, but were inspired by an American Enterprise Institute report. Soon after assuming office, Mullen told Keane, “I don’t want you going to Iraq anymore and helping Petraeus... You’ve diminished the office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs.” Keane worked around the ban imposed by Mullen by complaining to Vice President Dick Cheney’s office, but, more importantly, Keane maintained a significantly lower profile and did not challenge Mullen publicly.

Second, while Admiral Mullen repeatedly noted the principle of civilian control of the military, he strived to limit American involvement in additional wars. One early statement in front of the Senate warned of how stretched the military already was: “In Afghanistan we do what we can, in Iraq we do what we must.” Mullen emphasized that while America “reached for the military hammer in the toolbox of foreign policy fairly often,” he needed to be “just as bold in providing options when they don’t involve [military] participation…even when those options aren’t popular.”

In Syria, we learned from Cheney’s memoir that in the summer of 2007 when the Vice President asked for a show of hands to endorse attacking a suspected nuclear reactor in Syria, Mullen’s hand did not go up.

In Iran, through in public debates to attack the suspected nuclear weapons program, Mullen constantly highlighted, “opening up a third front right now would be extremely stressful on us...and very difficult to predict.” Moreover, since a military attack alone would only delay a nuclear program, Mullen added in April 2010, “from my perspective ... the last option is to strike right now."

In Libya, when many wanted a no-fly-zone, Mullen conceded that, “we’ve...not been able to confirm that any of the Libyan aircraft have fired on their own people.” Once the intervention started, he avoided regime change language, stating that, “the goals of this campaign right now again are limited, it isn’t about seeing [Qaddafi] go.” When the White House said there were no “hostilities” in Libya, Mullen countered: “We got a significant level of hostilities in a place like Libya.” Later, as a NATO spokesperson claimed, “There’s definitely no stalemate,” Mullen admitted: “We are generally in a stalemate.”

Finally, Admiral Mullen should be remembered for his willingness to publicly and clearly take a position on controversial topics that were not always directly under the remit of the chairman. Moreover, once he stated his opinion, he would repeat it when questioned, and amplify it through Facebook, Twitter, multiple appearances on Sunday morning talk show, and even Jon Stewart (three times). While there are few topics that Mullen did not address while serving his two two-year terms, upon reflection five stand out:

- On repealing Don’t Ask Don’t Tell: “It is my personal belief that allowing gays and lesbians to serve openly would be the right thing to do. No matter how I look at this issue, I cannot escape being troubled by the fact that we have in place a policy which forces young men and women to lie about who they are in order to defend their fellow citizens.”

- On military public relations efforts, aka “Strategic Communications: “Most strategic communication problems are not communication problems at all. They are policy and execution problems…There has been a certain arrogance to our “strat comm” efforts. We’ve come to believe that messages are something we can launch downrange like a rocket, something we can fire for effect. They are not.”

- On reading the notorious Rolling Stone article that featured Gen. Stanley McChrystal and his staff: “McChrystal is a friend. He’s a fine soldier and a good man. But I cannot excuse his lack of judgment…or a command climate he evidently permitted that was at best disrespectful of civilian authority…Honestly, when I first read it, I was nearly sick.”

- On the national debt, Mullen first made the remarkable assertion in August 2010 that, "The most significant threat to our national security is our debt.” This position has become conventional wisdom among military officials, and was recently echoed by the incoming Chairman, Gen. Martin Dempsey.

- On the threat he worries about most upon leaving office: “The single biggest existential threat that’s out there, I think, is cyber…Cyber actually, more than theoretically, can attack our infrastructure, our financial systems…There are countries who are very good at it. More than anything else that is the long-term threat that really keeps me awake.”

More than any other chairman, one theme that ran through Mullen’s comments was that the military should play an essential role in preventing conflict. He stated: “There isn’t a fight that I’m in that I’m not asking the question, ‘What could we have done to avoid this?’ Or, ’What can we do to avoid this in the future in terms of the kinds of things that we see?’”

In May, Mullen acknowledged: “I think that is a noble goal that all of us should seek, to end wars and prevent wars as much as possible.” An optimistic declaration from a combat veteran with forty-three years of active-duty service. Thus, we say farewell and thank you to Admiral Michael Mullen for your service, and for being honest in an age when America’s leaders say everything short of what they believe.

Online Store

Online Store