Can the Oil Threat Spare Saudi Arabia From America’s Wrath?

Threatening a price hike might work in the short term, but it would come with serious costs to the kingdom’s reputation as a moderating influence on oil markets.

Originally published at Politico

October 18, 2018 10:18 am (EST)

- Article

- Current political and economic issues succinctly explained.

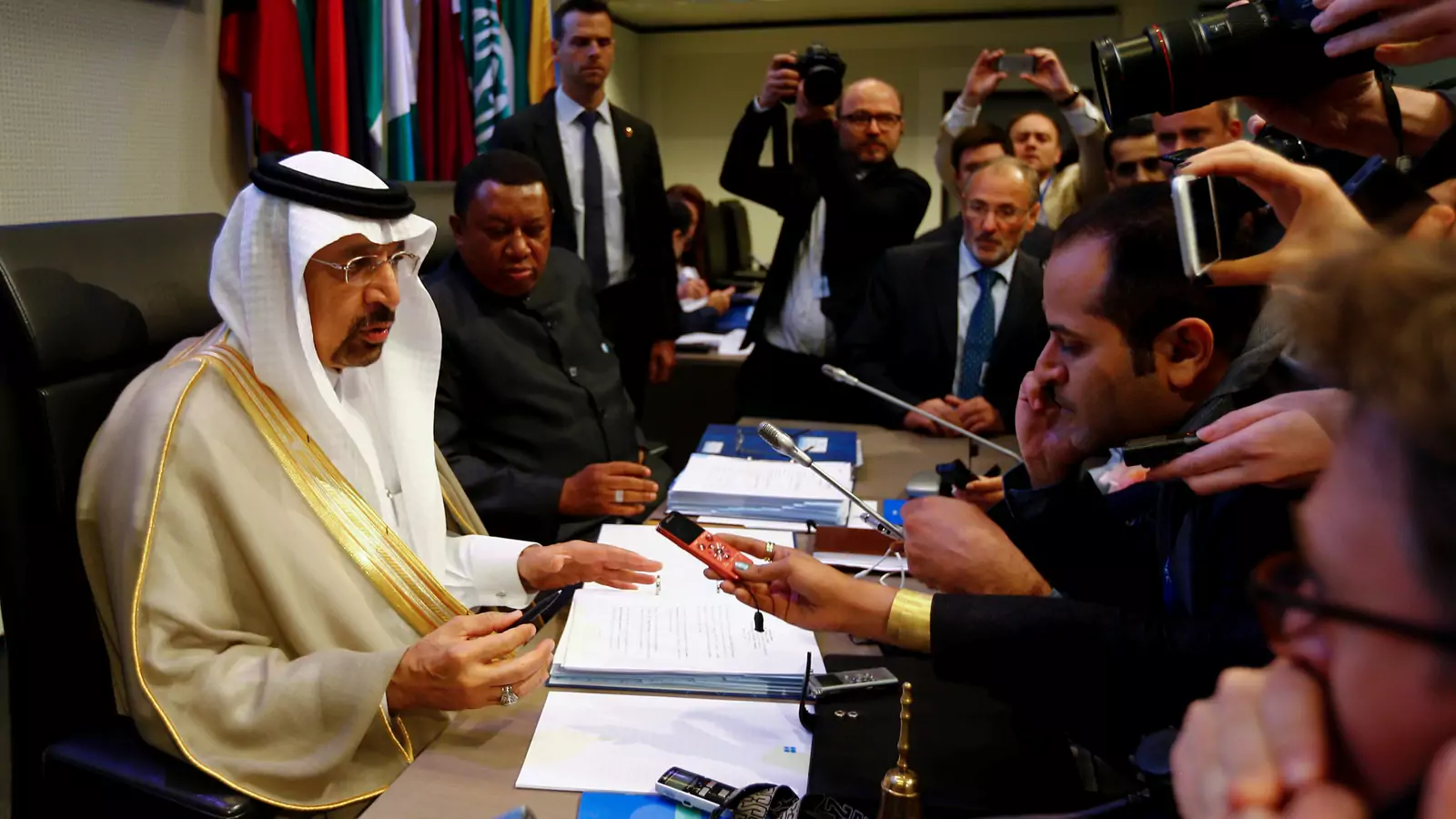

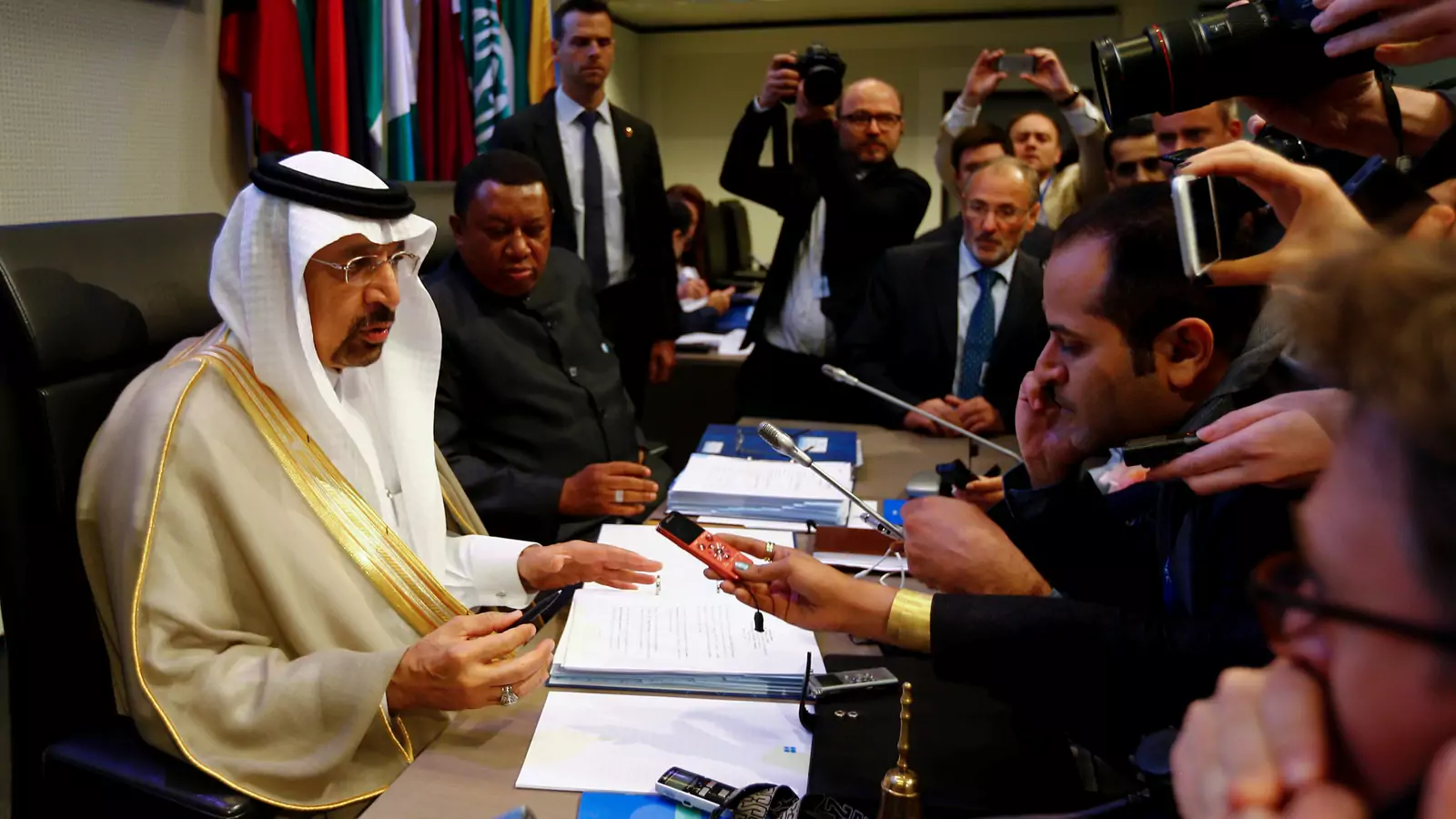

At an oil executive gathering in India earlier this week, Saudi Energy minister Khalid Al-Falih reminded the world that Saudi Arabia acts as the “central bank of the oil market” to help keep supply and demand in balance. His statement might have seemed innocuous enough, had it not come amid escalating rhetoric in the ongoing controversy surrounding the disappearance of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi. In what was clearly a swipe at President Donald Trump, who has been complaining of late about oil prices, the minister added, “We expect and demand that Saudi Arabia’s efforts be acknowledged. These supply disruptions need a shock absorber. The shock absorber has been to a large part Saudi Arabia.” He noted that oil prices could easily have reached over $100 a barrel, but for Saudi efforts.

As an oil analyst, I don’t doubt that the minister is correct in this assessment of Saudi Arabia’s influence on prices. Trump also appears to agree, since he has been tweeting at Riyadh to do something more about high oil prices for weeks. Issuing a not-at-all veiled threat to leave the Saudis to fend for themselves, the president even went so far as to say King Salman wouldn’t last two weeks without U.S. military support.

More on:

At another moment, Saudi Arabia’s reactions might have seemed just innocuous rejoinders in a war of words. But in the context of a tightening world oil market, they belie a serious, extortionate threat to use their important position in oil to retaliate against any policy (for example, a U.S. congressional exercise of the Magnitsky Act) that might be considered to dissuade Riyadh from future extra-territorial pursuit of journalists or dissidents. That makes the stakes very high—regardless of the improving prospects for diplomatic de-escalation—not only for the immediate welfare of the global economy, but also for the kingdom’s future role as the trusted keeper of stability in global oil markets.

Saudi Arabia has often acted to calm oil markets ahead of troubled times. Notably, the kingdom even increased its oil exports in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks to reassure a concerned global economy that there would be no geopolitical implications for oil. The Saudis took similar action around the time the United States invaded Iraq. But in the runup to the U.S. decision to tear up the Iranian nuclear deal and reimpose oil sanctions on Iran, Saudi Arabia initially discussed a deal with Russia to cut output so as to boost oil prices to $80 or higher. That precipitated a tweet storm from President Trump against the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries and its most important member, Saudi Arabia, in particular. One can only assume the White House was appalled by the Saudi ingratitude that it was showing on Iran. By contrast, Saudi Arabia had increased production when President Barack Obama was preparing to add sanctions against Iran back in 2012.

Already, U.S. sanctions against Iranian oil exports have removed 1 million barrels to 1.5 million barrels a day in sales to Europe, Japan and South Korea this fall, pushing oil prices up. Saudi Arabia, after much jawboning from the United States and even from India, increased its exports, replacing those barrels. Still, crude oil prices continued to lurch above $80 a barrel recently as analysts started crowing about how Saudi Arabia was now producing near its maximum, leaving little cushion should a new geopolitical supply disruption emerge.

For barrel-counters, oil demand has averaged about 100.7 million barrels per day this fall, while recent global supply is running roughly equal, at 100.6 million. Oil stocks typically are replenished this time of year, ahead of winter. But given the current tight balance between supply and demand, analysts are expecting that the usual pre-winter seasonal buildup of an oil-inventory cushion might not happen this year. For example, respected forecasters Cornerstone Macro project oil inventories will decline by 500,000 barrels between September and year end. New problems in any of a host of places, such as Libya, Nigeria, Venezuela or southern Iraq, could deepen the shortfall.

This tightening market situation is the backdrop to Saudi Arabia’s intemperate reference to the oil weapon. Officially, the government was vague, saying it would respond with “greater action” to any economic sanctions threat against it and reminded of its vital role in the global economy. But it presumably authorized a more strident, explicit op-ed on the government-controlled news service Al-Arabiya that warned of retaliation if any U.S. sanctions were imposed on Saudi Arabia.

More on:

“We will be facing an economic disaster that would rock the entire world,” well-known Saudi media figure Turki Aldarkhil wrote. “If the price of oil reaching $80 angered President Trump, no one should rule out the price jumping to $100, or $200, or even double that figure.”

Talk like that makes one wonder: Given the current tight oil market, can Saudi Arabia hold the world hostage, as it did during the 1973 oil embargo?

Although the immediate crisis could possibly decompress with accountability within Saudi intelligence leadership, my sense of market conditions is that Saudi Arabia could absolutely wreak some havoc, but not for long. Removing oil from the current market could increase prices, perhaps precipitously—at least in the short run. Depending on how much oil was removed from the market and how the Trump administration responded regarding enforcement of Iranian oil sanctions, oil prices might briefly jump up sharply.

But western countries would almost certainly release strategic stocks (the G-7 unified statement on freedom of the press is salient) and, eventually, an easing of Texas pipeline bottlenecks by early 2019 would allow the flow of more U.S. tight oil to the global market. Higher prices would cause oil demand to fall, especially in the developing world. In other words, retaliating in the oil market could be a brief, Pyrrhic victory for Saudi Arabia, unless it were done in tandem with other important oil producers. For example, Moscow could inject itself into the situation by suggesting it could collaborate with Riyadh on any oil-supply cuts and try to elicit a pound of flesh from the U.S. or even China.

Several pundits have explained why unsheathing the oil weapon would not be in Saudi Arabia’s self-interest, and current oil prices, which have risen only modestly in recent days, reflect that belief.

Still, the threat itself matters. Its political damage has already been done. It’s hard to remain a central banker who inspires confidence after you have threatened to bankrupt your depositors. The kingdom needs to go to incredible lengths to retract this reckless impression before it sets into a permanent stain, or it may find that its customers will take concrete actions to remove the risk. Some countries were already looking closely at how to accelerate electric cars, alternative energy programs and other oil-saving measures in light of climate change. Now many more countries will have impetus to do so quickly.

Which is not to say the peril of an oil crisis is over. Nations and their leaders are not always out to make the sensible point. In today’s dangerous world, the exercise of raw power has been rewarded in multiple ways that cannot be quantified in light of national budgets or trade balances.

Online Store

Online Store