What to Expect From the ECB

More on:

I’d like to think that the ECB will surprise us tomorrow with a package that includes both a rate cut and measures to increase the flow of credit to the periphery. That could produce a meaningful easing of financial conditions and a weakening of the euro, both of which are constructive for euro-area growth.

A few points:

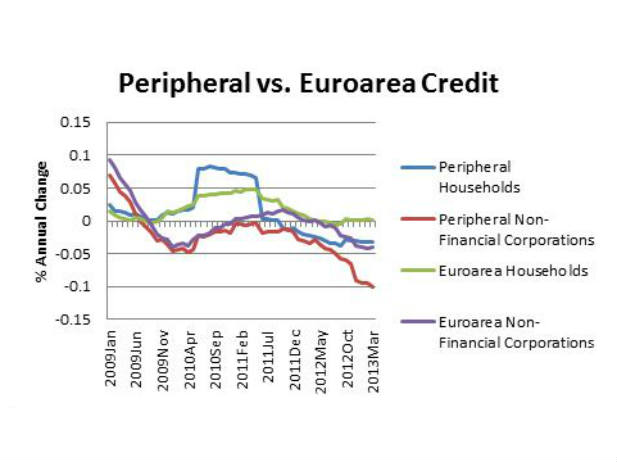

1. Markets now expect a rate cut, at a minimum. A majority of economists surveyed by Bloomberg expect the ECB to cut the benchmark refinancing rate to 0.50 percent from 0.75 percent. Weak April data, signals from the ECB that it is increasingly concerned about the downside risks, and a soft inflation outlook for the eurozone as a whole have moved expectations. (The ECB sees euro inflation at 1.6 percent this year and 1.3 percent in 2014, and that was before the latest soft price data.) In addition, credit data continues to disappoint.

Source: Eurostat

2. Measures to ease credit conditions for SMEs may be close. A trial balloon last week from Executive Board Member Yves Mersch suggested the ECB could provide liquidity support for the development of securitized pools of small business loans made by development banks. This is one of a number of ideas for spurring small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) lending in the periphery. The Bank of England’s (BoE’s) Funding for Lending scheme is another possible model (though there isn’t convincing evidence so far that the BoE scheme has worked). It’s unclear any of these initiatives are ready to go forward, though.

Below is a nice chart from Morgan Stanley pointing out the importance of SME lending for periphery growth. (It shows that countries with the highest SME lending rates have the highest SME share in gross value added, or GVA.)

3. But the case for a rate cut has its critics... My colleagues Benn Steil and Dinah Walker summarize the case for caution. The broken transmission mechanism could mean that those southern European countries with deflation and negative growth may see little direct benefit from a rate cut, while the north already has inflation close to or above the ECB’s target. The counter argument, which I find compelling, is that the first-order effect of the rate cut is to reduce funding costs of those banks (notably Italian banks) that rely on funding from the ECB. I do believe that, with demand faltering across the eurozone and overall inflation below target and expected to fall, the risks to price stability in the north are very limited. Further, over the longer term, these types of inflation differentials also contribute to the needed rebalancing of demand.

4. Quantitative easing as the endgame? Gavin Davies’s summary of the options for the ECB gets to the same bottom line that I have. An easing of collateral requirements can have a meaningful impact, but ultimately the ECB may need to consider a full-out quantitative easing if it is to meaningfully boost the size of its balance sheet. As Steve Englander among others has highlighted (chart below), the relative size of the balance sheet is a good indicator of exchange rate moves. It’s hard to see a return to growth in the periphery without some contribution from external demand.

Some progressive critics of austerity will argue that when an economy is at or near the zero lower bound, the effectiveness of monetary policy is diminished and more of the burden needs to be carried by fiscal policy. My problem with that line of argument is two fold: first, in Europe at least, politics as well as the reality of unsustainable periphery debt and finances limit the amount of fiscal easing that is possible; and second, the ECB hasn’t done all it can do--far from it.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store