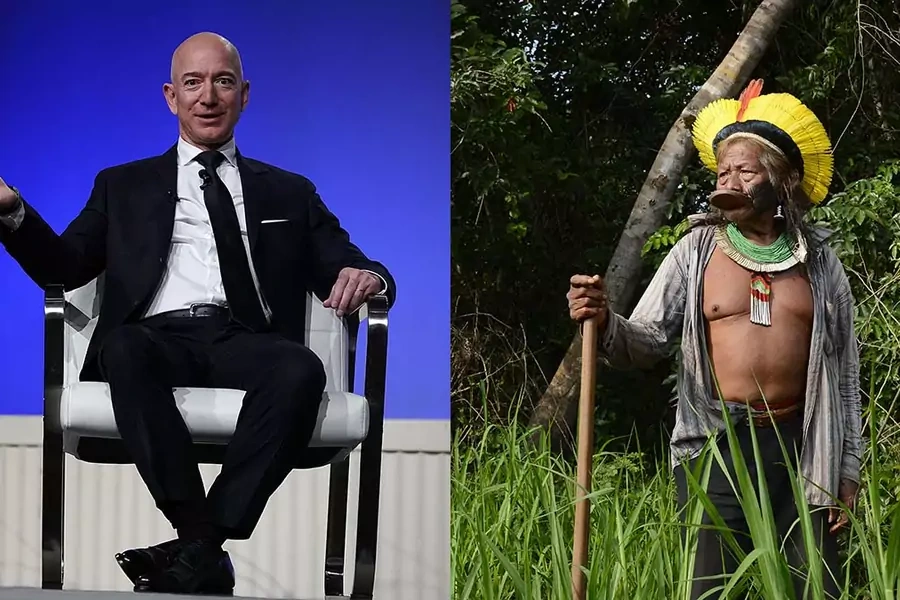

A Tale of Two Amazons

In early January, e-commerce giant Amazon.com reached a historic milestone, inching past Microsoft to become—for a brief period, at least—the world’s most valuable public company. Since opening for business in July 1995 as “Earth’s Biggest Bookstore,” the company has expanded its product lines to become not only the dominant online retailer and logistics service but a major player in cloud computing, thanks to its burgeoning Amazon Web Services (AWS) division. Combined with its purchase of Whole Foods and its more recent launch of Amazon Go, the company continues its relentless drive to become the digital era’s “everything store.”

But what of the other Amazon—the wild wonder of the natural world? The world’s largest tropical rainforest is faring worse than the corporation that shares its name. Last year, deforestation of the Amazon reached a ten-year high, as farmers, loggers, miners, ranchers, and settlers denuded an area more than half the size of Jamaica. The region’s future looks even grimmer. Earlier this month, Brazil swore in its new, populist president, Jair Bolsonaro. He has pledged to roll back environmental protections and accelerate the economic exploitation of the Amazon, while appointing a foreign minister who dismisses climate change as a “cultural Marxist” plot. Last week in Davos, Bolsonaro reassured the assembled plutocrats that he cares about the environment. His policies say otherwise.

More on:

These twin developments—the extraordinary growth of a cutting-edge company and the clear-cutting of much of the planet’s most biodiverse ecosystem—seem unconnected. But their juxtaposition offers an opportunity to consider what the global economy values, what it doesn’t, and what this portends for our future. Comparing the two Amazons underscores a duality of contemporary life on our fragile and shrinking planet: At the same moment that technological innovations are bringing us closer together, our unsustainable patterns of production and consumption are threatening the planetary life support systems on which we depend.

Sizing Up the Competition

When it claimed the title of world’s most valuable company, Amazon had a market capitalization just under $800 billion, a hair ahead of Microsoft ($789 billion), with fellow tech giants Alphabet ($745 billion) and Apple ($702 billion) close behind. That valuation was larger than the gross domestic product of all but seventeen of the world’s countries, placing it just above Saudi Arabia and just after the Netherlands. Jeff Bezos, the company’s owner, is now the world’s richest person by far, with an estimated net worth of $138 billion. The corporation employs more than 600,000 people, about double the number it employed two years ago. Nearly two thirds of U.S. households are registered with Amazon Prime.

The scale of the Amazon is even more impressive. Nearly the size of the continental United States, it encompasses 5.5 million square kilometers—more than all other tropical rainforests combined—and at least one estimate places the number of its individual trees at 390 billion. Although two-thirds of the Amazon is located within Brazil, it also spans large swathes of Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana. It includes hundreds of thousands of species of plants and two and a half million species of insects, with many new ones being discovered every year. Precipitation over the rainforest is extraordinary, reaching up to 20 billion tons of water daily—more than the Amazon River (the company’s namesake) discharges into the Atlantic Ocean each day.

Calculating Their Worth

Amazon’s $800 billion market cap is remarkable. From a conventional price-earnings (P/E) ratio perspective, this valuation seems hard to justify. In mid-December, for example, Amazon’s P/E ratio was 89.19, nearly six times higher than Apple’s (13.89). Investors clearly anticipate that aggressive expansion today will translate into high profits tomorrow. While this faith may be misplaced, long-time shareholders have ample reason to be pleased. A $100 investment in the company when it went public in 1997 was worth nearly $64,000 twenty years later.

More on:

Calculating the value of the Amazon is trickier. It requires looking beyond the immediate gains from extractive industries like mining and timber to consider the ecosystem services that the rainforest provides–not only for the communities and nations situated within and adjacent to its confines but the world at large. Among the most important of these services is mitigating climate change by sequestering carbon dioxide emissions. In a recent study published in Nature, scientists estimated the total annual value of services provided Brazil’s portion of the Amazonian rainforest—including reduction of greenhouse gases, regulation of the local climate, and sustainable extraction of non-timber forest products (e.g., nuts and rubber)—at $8.2 billion annually. Although private interests may have a financial interest in razing the forest, Brazilian society would often gain more economically, even in the short term, by leaving the forest intact. Notably, the study did not even begin to address the massive economic value of the region’s biodiversity, including the medicinal potential of plant species—only a tiny fraction of which have been analyzed by bio-prospectors for pharmaceutical applications.

Weighing Their Political Influence

In contrast to Google, which initially adopted the motto “don’t be evil,” Amazon has never cloaked its ambitions in touchy-feely techno-utopianism. And it has not been shy about defending its interests in Washington, either, spending $3.63 million in federal lobbying in the third quarter of 2018. It is no accident that the company chose to locate one of its two new headquarters in Northern Virginia, across the Potomac from Congress and the White House and just downriver from the Pentagon, potentially one of its biggest customers. Nor is it incidental that Bezos owns the Washington Post, one of the most influential media outlets in the nation—even more so the nation’s capital. Beyond placing the company in a position to compete for lucrative government contracts, from face recognition applications to the Pentagon’s $10 billion JEDI cloud contract, Amazon’s growing political heft positions it to resist antitrust efforts, whether from a resentful Donald Trump or from legislators and judges who believe that it is abusing its monopoly position and needs to be broken up.

The Amazon’s political influence is more nebulous and tenuous—and it shows. A generation ago, pop culture celebrities like Sting aligned themselves with indigenous tribes and local environmentalists to bring the despoliation of the rainforest to global attention. This transnational activism paid off, albeit gradually, helping encourage the Brazilian government to slow the pace of degradation. Between 2005 and 2012, Brazil reduced forest clearance by 80%. Even with a recent uptick, deforestation today remains sharply below the early 2000s. All that is poised to change, however, thanks to the arrival of the nationalist Bolsonaro. Beyond reneging on Brazil’s pledge to host the 2019 Conference of Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, the new president—whose “Brazil First” platform declared that existing environmental regulations were “suffocating the country”—promised to fold the nation’s ministry of the environment into the ministry of agriculture—despite agriculture being the largest source of deforestation. His intent, indigenous groups and conservationists fear, is “to transform the Amazon into commodities for export.” Even before he took office, illegal loggers had “interpreted Bolsonaro’s comments as a green light to start chopping,” the Washington Post reported. “We measure deforestation through satellite images from the Amazon,” Marcio Astrini of Greenpeace told that newspaper. “But if we had a satellite measuring the cause of that deforestation, it would be pointed at Brasilia.”

The Amazon has already lost a fifth of its forest cover over the past fifty years. This has disrupted regional precipitation patterns, contributing to droughts in Brazil’s southeast. But the ecological impacts extend far beyond South America. Globally, deforestation is responsible for some twelve percent of human-generated greenhouse gas emissions. Scientists estimate that the Amazon today is absorbing less than half the carbon dioxide that it did just two decades ago, as a smaller rainforest provides a smaller carbon sink, as felled trees return their carbon to the atmosphere, and as desiccated trees absorb less CO2 than healthy ones. If these trends continue, they warn, the Amazon could eventually emit more carbon dioxide than it absorbs.

Even as the world hangs over every detail of the divorce of Amazon’s founder, speculating as to how his personal fortune might be divided, we neglect the health of the far more valuable Amazon rainforest and the ecosystem services it provides. In our relentless obsession with accumulating financial capital, material comfort, and convenience, we have given short shrift to the natural capital that keeps our biosphere functioning and allows us to survive and thrive. These attitudes are not sustainable.

Online Store

Online Store