Syria in Play?

More on:

It seems from my twitter feed and news reports that Syria might be in play. Amid a complete media blackout, best that anyone can tell, Syrian security forces have killed at least 12 and wounded hundreds in the southern city of Daraa—the scene of three previous days of fierce protests. Analysts have been wondering why the surge of anti-government protest had—until late last week—not seemed to have reached the Syrian border. It’s not that there isn’t discontent in Syria. Indeed, the country has many of the same problems (in spades) as the other countries experiencing unrest. Most salient is the Assad regime’s almost exclusive reliance on force to keep the population under control. As we saw in Tunisia and Egypt, once the fear factor melts away some sort of upheaval is more than likely to follow.

I am not saying that revolution in Syria is going to happen. There are some analysts, particularly Josh Landis who blogs at “Syria Comment” who indicate the origins of the Daraa protests and their implications are not what they appear to be, either from afar or the strawhole of twitter. That may very well be the case. Josh knows a lot about Syria. I wonder, however, whether the regime’s use of violence will not have the opposite of the intended effect. Rather than intimidating protestors, perhaps the violence will galvanize more Syrians to take to the streets demanding change. That is what happened in Tunisia, Egypt, Bahrain, Yemen, and to a certain extent Libya. We’ll just have to wait and see whether the revolutionary bandwagon gets rolling in Syria; there’s really no way to predict.

That said, here are my two preliminary thoughts should Syrians manage to crack the lid on the Assad regime:

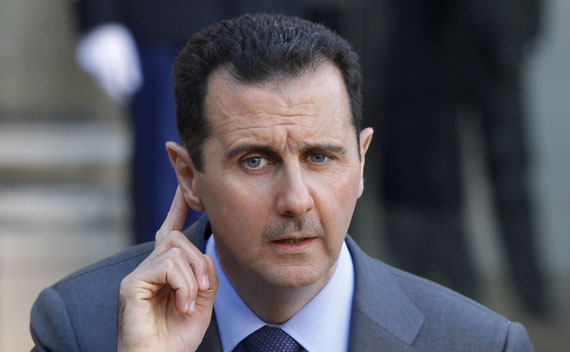

1) Bringing down President Bashar al Assad and the regime he presides over would be as big and important as Mubarak’s fall. In the abstract, Syria should not be an influential country. It doesn’t have much oil, its military is unable to project power other than in Lebanon, its economy is a mess, and its official ideology is…well, repulsive. In reality, though, the Assads have managed to make something out of nothing through their uncompromising position on Arab-Israeli conflict, Syria’s alliance with Iran and Hizballah, Damascus’ influence over Lebanese politics, and the regime’s willingness to use force against their opponents and average Syrians alike. If a new, decent government emerged in Syria—by no means a guarantee, see point 2—it would alter the regional balance, improve the prospects for regional peace, and, importantly, allow Syrians to live and prosper without the pervasive threats of a fearsome national security state.

2) Change in Syria, as appealing as it is, does pose a number of serious challenges. After all, the country manifests many of the same problems of two of its neighbors—Lebanon and Iraq—though perhaps not as pronounced. Although the overwhelming majority of Syrians are Arabs (90 percent), there are important ethnic minorities, notably the Kurds. There are also splits along sectarian lines. The Assads are Alawis, which make up 12 percent of 22.5 million Syrians, Christians account for 10 percent, while Sunnis are an overwhelming 74 percent of the population. Smaller groups, including a few Jews and Yazidis, comprise the remaining four percent of Syrians. The breakdown is probably not as important as what these groups have at stake, especially the Alawis. The Assad era has been very good for the Alawis. As a result, they are unlikely to give up their privileged position in Syrian politics without much of a fight. This is not to say that the Alawis have excluded the Sunnis. There are many prominent Sunnis connected to the regime through politics and business. Still, if the political order began to crack under the weight of demands for change, you have to wonder how long before the majority runs from the minoritarian regime. This may be one reason why Bashar was so quick to use violence against the protestors in Daraa.

So much has happened in the Middle East over the course of the three months, that it is hard to believe that Syria is immune to change. Yet it’s not all rainbows and unicorns in the region. It’s entirely possible that Assad will learn the reverse lessons of Egypt and Tunisia and shut protests down before they can even begin in earnest or that he employs massive force to undermine demonstrations should they get going. There is precedent for this, of course. Indeed, when I think of 1982 and 25,000 dead in Hama, I shudder.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store