Regulating sovereign wealth funds: does the US have any leverage?

More on:

Bob Davis’ Wall Street Journal article - which reports that the US Treasury is pushing Singapore and Abu Dhabi to increase their transparency and to signal that their funds will be managed commercially as part of the IMF’s effort to develop best practices - has prompted a flurry of online commentary.

Both Felix Salmon and Yves Smith doubt that the US has any real leverage over the sovereign funds.

Felix highlights the meaning of the term sovereign: sovereign funds are not accountable to any government other than the government of the country that is sponsoring them.

"Sovereign" means it’s not up to anybody else what you are or are not allowed to do.

Yves, echoing Zachary Karabell, argues that the debtor - and in today’s global financial system the US is the debtor - cannot set the rules of the game, but rather has to accept a global financial system defined by the creditors. He writes:

Consider the elements of fantasy at work in this discussion over these efforts to set guidelines on SWF investments:

1. We are pretending that a large stake in and of itself won’t lead to influence

2. We are pretending that we have negotiating leverage in this matter. We don’t. We need the dough desperately. Unless we get our saving rate up to make ourselves more independent (which will almost certainly lead to a recession or a very prolonged period of low growth), we are in no position to place restrictions on capital inflows (except now and again, for show)

3. We are pretending that any commitments made are meaningful. Let’s say the SWF decide that it’s politically expedient to play nice and agree to certain measures, like allowing for a certain amount of transparency and publishing their fund objectives, which will of course be to earn a certain level of financial return and will have nothing to do with getting access, say, to resources or technologies. First, there is no way to make the funds conform to their statements. Second, even if the funds are completely sincere when they make these representations, a change in leadership can lead them to repudiate their former policies, after they have acquired substantial positions.

So these negotiations are really theater for the benefit of the American public.

In my view, both understate the United States’ leverage.

Sovereignty cuts both ways.The US cannot force Abu Dhabi to reveal the size of its fund. But if the US wanted to publish a publicly available estimate of Abu Dhabi’s fund, I suspect it could. It is a sovereign country, after all. And, for what it is worth, I would bet ADIA has significantly less than the commonly cited $900b figure, which I think originated with Morgan Stanley. The US could also publish an estimate of the GIC’s size.

The US cannot require sovereign funds to invest in certain ways. But it can regulate the type of US assets sovereign funds can buy. In fact, it already does. Certain parts of the US economy are off limits to any large foreign investments. Media companies for example. No sovereign fund could buy a controlling stake in say Boeing. CFIUS wouldn’t allow it. Those restrictions could be far more intrusive. The US could pass a law mandating that CFIUS review any purchase of more than 1% of a company’s equity by a sovereign fund, or requiring such a review by any fund that doesn’t meet certain standards of disclosure.

China doesn’t currently allow US hedge funds, private equity firms or banks unfettered access to its domestic market. That is its sovereign right.

Of course, just because the US could pass such a law doesn’t mean it should.

A law limiting the investments of non-transparent sovereign funds in the US market would force ADIA to sell a fairly large amount of stock, and ADIA and the GIC to divest from several large US financial institutions. It would have real consequences.

Felix would also note there are ways of skirting such regulation. Sovereign funds could put money in a London or Swiss hedge fund that the fund effectively controls. Or, more easily, a fund could buy an equity derivative providing them with the upside from any rise in the price of a given stock. Several funds already do this. These moves could though in turn invite a broader regulatory response as well, one that would make the US financial system very uncomfortable.

Or a non-regulatory response. The state of California, for example, is considering legislation that would require that its state pension funds divest from private equity funds that are partially owned by governments with less than pristine human rights records.

What of Yves Smith’s argument, namely, that in the global financial system, money is power - and the US no longer has the money.

I have some sympathy for his point of view.

A 9.9% stake gives an investor a bit of potential influence over a firm, even in the absence of a board seat. The process of selling equity to foreign governments to fund both the current account deficit and ongoing portfolio diversification by private US investors implies some loss of economic control. I also agree that nothing prevents a change in government from changing the way a sovereign manages its assets (PDVESA is a case in point).

But I also suspect that the United States has a fair amount of leverage, despite being a debtor.

The US is after all a unique debtor. Other countries haven’t been financing the US because the US offers a great return. The dollar hasn’t held its value relative to the euro, relative to oil, relative to wheat or relative to most metals over the past few years. It is unlikely to hold its value relative to most emerging market currencies. Yet the US still has attracted the financing it needs. The worse the dollar does, the more dollars foreign governments seem to want to buy.

There simply aren’t that many places in the world that can absorb the emerging world’s surplus savings.

Sovereign funds could try to dramatically increase their holdings of European assets (as could central banks). That would have one of two effects. It could push the euro and indeed all European assets up in price, with the euro’s rise irritating European governments already worried by its strength. Or it could lead Europeans who sell to emerging market sovereign funds to buy more US assets, limiting the impact of the shift in sovereign demand on market prices. More sovereign investment in Europe would lead to more private European investment in the US.

Sovereign funds could try to increase their investments in emerging markets even more than they already are. But those markets are small. Such inflows could have one of three effects: an emerging economy like Thailand could allow its exchange rate to appreciate and start to run current account deficits, it could intervene in the foreign exchange market to avoid such appreciation (and in the process finance the US) or it could slap on capital controls designed to deter ongoing inflows. Thailand thought it was attracting too much (private) investment about this time last year ..

Bottom line: emerging economies are building up their foreign assets because of a domestic policy decisions - whether to invest the fiscal surplus from the commodity boom abroad to limit the appreciation of their exchange rate. Unless they change those policies they are forced to invest abroad. Those surpluses are too large to be absorbed by other emerging economies (especially so long as emerging economies shy away from current account deficits) so they have to flow to the US and Europe. And if emerging economies stopped buying US assets and threw the US into a recession, that would reverberate back onto their own export sectors.

Emerging economies are stuck too.

The evidence?

China is in all probability buying far more US bonds now than it did back before the US Congressional pressure thwarted CNOOC’s bid for Unocal, simply because the amount of dollars China has to buy to keep its exchange rate from appreciating has gone up.

And the Gulf is likely buying far more dollar assets now than they did before the US blocked Dubai Ports World. Both because of higher oil prices and because of its ongoing dollar peg. Say a major Gulf fund - Qatar - opts to invest more in Europe and less in the US. And let’s assume its decision adds to pressure on the dollar. What then happens? Well, Qatar’s own exchange rate would depreciate along with the dollar - and the misalignment would likely attract large speculative inflows. Its central bank would have to buy more dollars to keep its exchange rate from rising. And those dollars would have to be invested in the US to avoid putting further pressure on the dollar.

The financial flows that finance the US deficit reflect policy decisions that require the buildup of offshore assets, whether to prevent exchange rate appreciation or to avoid the inflationary impact of suddenly spending the entire commodity windfall.

The emerging world’s unwillingness to adjust those policies gives the US leverage. Europe too. SWF inflows into the eurozone finance more private European investment abroad, not a current account deficit.

The fact that the funds managed by sovereign fund reflect broader policy decisions has another implication. Sovereign wealth funds are not - contrary to the often-make argument - a new source of liquidity for US and European markets. Not in aggregate.

As Ted Truman notes, if sovereign funds did not invest in US and European banks, they would be buying other US and European assets. Their decision to invest in the banks provided the banks a new source of risk capital, but it reduced the "liquidity" available for other markets. By the same token, to the extent that central banks - which manage far more sovereign money than sovereign wealth funds - have piled into Treasuries and Agencies, they have added to the liquidity of those markets but removed a potential source of support from other markets.

To put it differently, sovereign funds and central banks have never had more money to play with than they have now. And I suspect that a broad range of markets has never been less liquid than they are now.

So does the debate over transparency matter, or is it just window dressing?

I think it matters.

There is a reasonable chance sovereign funds will get big fast, and will soon account for the majority of foreign purchases of US equity. The emerging world has the biggest chunk of the world’s current account surplus. It likely added around $1.2 trillion to its reserves and maybe $200b to its sovereign funds. And not all of the money flowing into sovereign funds was invested aggressively - total sovereign equity purchases were probably less than $150b (counting some purchases from central banks) and total purchases of US equity were likely under $75b. Total portfolio equity inflows (per the TIC data) for 2007, official and private, were only $200b. A world where emerging market governments are adding $1.2 trillion to their sovereign wealth funds rather than $1.2 trillion to their reserves and buying say a trillion dollars worth of equities rather than a trillion dollars worth of bonds is very different than today’s world.

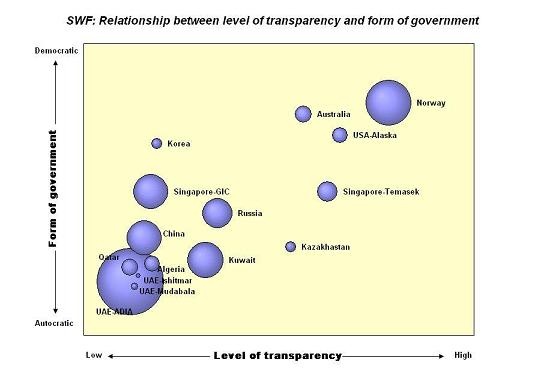

Moreover, the funds likely to grow the most rapidly are - setting Norway’s funds aside - funds from countries that aren’t very democratic. There is - as the following superb chart by the CFR’s Arpana Pandey shows - a strong correlation between a fund’s level of transparency and the political structure of the fund’s host country.

The level of transparency comes from the Truman index; the form of government from the Economist Intelligence Unit’s democracy index; the estimates of the fund’s size come from Standard Chartered.

The US and Europe are in effect asking the emerging markets now adding to their assets most rapidly to set up institutions to manage their sovereign funds that are more like the existing sovereign wealth funds (and for that matter state pension funds) of the major democracies and less like the sovereign wealth funds of non-democratic countries. In other words, some sovereign funds are being asked to conform to the norms of the societies they are investing in rather than the norms of the societies they stem from.

Not fair, you might argue. Why should the US try to push other countries to adopt its norms? It is their money after all. True. But the US is also being asked to accept a far higher level of government ownership of the US equity market than has been the case previously, and probably a higher level of government ownership than most Americans want. The US is also being asked to change.

The overarching judgment - which seems right to me - is that there is no political consensus that will accept the rapid growth of sovereign claims on the US and Europe if the big and rapidly growing funds remain clustered at the lower left hand corner of the transparency v democracy graph.

It is easier to change the level of transparency of a fund than to change a country’s political system.

That said, even if sovereign funds radically increase their transparency, the huge shift in sovereign demand toward equities that some banks are forecasting is likely to have an impact on the market’s overall dynamics. Mark Carney of the Bank of Canada has highlighted how sovereign demand for safe bonds changed the overall dynamics of the bond market. A comparable increase in sovereign demand for equity reasonably can be anticipated to have a large impact on the market. Anticipating just how that will play out, though, is hard.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store