The Perils of the Midterms: For Both Parties, and for the United States’ Political Future

By most accounts, Republicans are poised to take control of the U.S. House of Representatives, and possibly the U.S. Senate, following the midterm congressional elections in November. If current prognostications hold, the GOP will pick up between twenty and thirty-five House seats, giving them, at the high end of that range, their largest majority since the late 1920s. An overall reading of the numbers, along with Democrats facing serious structural realities and national headwinds, suggest that the current 50-50 Senate Democratic majority is also in serious jeopardy.

But this isn’t a post about the midterm horse race, or an analysis of what this might mean for policy in the next Congress—it’s an early warning to both parties to tread cautiously in their reactions to what might occur November 8. Both sides stand to misread what voters are telling them with their ballots—or lack of ballots—and the consequences of taking the wrong message from the public are far more serious than simply who controls the legislative branch for the next two years.

More on:

If the electoral scenario described above comes to pass, many Republicans will crow about their “victory,” considering the midterm results an affirmation of their recent course, and, by extension, a verification that Trumpism remains not only viable, but advantageous for their future. While it’s true that some Donald Trump−backed candidates have lost their primaries, he’s still batting roughly .700 in races not involving incumbent Republicans (a more reliable measure given that incumbents typically have ample advantages regardless).

But there’s a big difference between winning—having voters saying “I like X or Y about Republicans”—and simply not losing. And the reality is, while the midterms may provide Republicans the appearance of victory, the elections’ results are far more likely to be about Democratic defeats. Despite poll after poll showing Republicans en route to a sizable majority, numbers released the week before last showed that congressional Republicans have only a 23 percent approval rating, with 68 percent of respondents registering their disapproval. Being considered the lesser of two evils is not reason for celebration, and certainly shouldn’t be taken as confirmation that the party is on the right track.

Democrats risk taking their own ill-founded lessons from the midterms. When Republicans lost presidential races in 2008 and 2012 (with Democrats simultaneously picking up congressional seats), many on the right made the case that their candidates were simply “not conservative enough.” Had Republicans run further to the right, their argument went, the party would have been rewarded with wins. A similar dynamic is likely to occur among many Democrats following midterm defeats. The party’s harder left edge, once confined to Dennis Kucinich rallies during the Iowa caucuses, has gone fully mainstream within the party, with entities like “The Squad” wielding more and more influence. While the argument that the Democrats should track further left may be seductive to a growing number in the party, broad opinion polling shows that this isn’t really a reasonable course. President Joe Biden and his advisors no doubt know this, but with recent numbers showing Biden doing exceptionally poorly among Democrats, and with 94 percent of all voters under thirty (who tend to skew leftward) saying they’d prefer a different candidate, moving to the center is a risky political proposition.

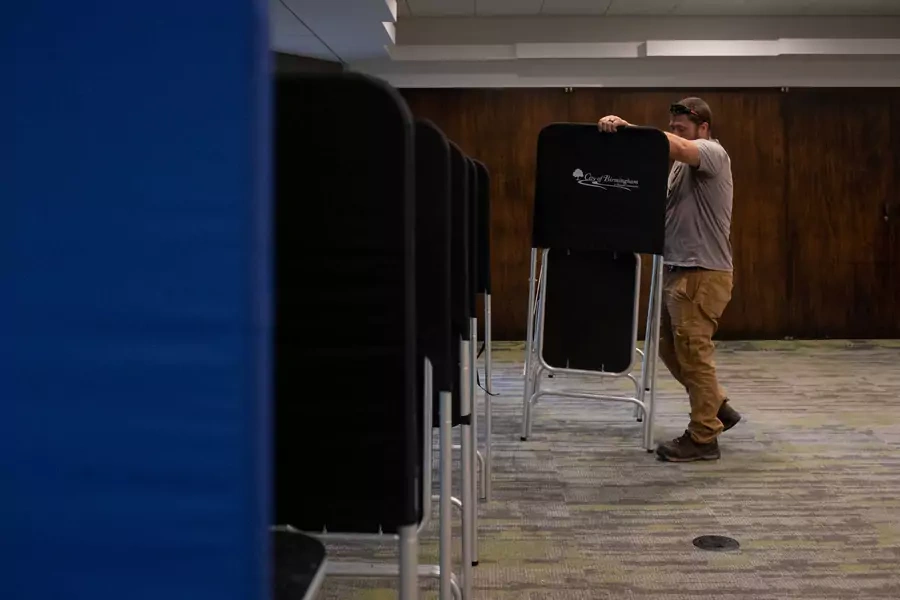

On the Democratic side, an even more toxic temptation will be to blame their losses on state elections rules that they’ve labeled “voter suppression” over recent months, claiming these rules decided the elections’ results. To be clear, for the purposes of this discussion, I am not taking a position one way or another on these laws. They are an enormously complex patchwork of complicated efforts at the state level requiring a far more in-depth analysis. But regardless of how one views those actions in the states, the reality is that the Democrats’ broad disadvantages—inflation at a level not seen since the early 1980s, Biden’s striking unpopularity, a raft of retiring incumbents, and the fact that any president’s party tends to lose around two dozen seats in midterms—indicate that they are on track for significant losses, new election rules notwithstanding. Trump and the majority of House Republicans seriously threatened the foundations of the American democratic system and rule of law with their odious “stop the steal” efforts in the wake of the 2020 election, with disastrous results. For Democrats to further this erosion in 2022—with what could be scant evidence that those laws changed the outcome in any races—is playing with genuinely dangerous fire.

Why worry about this now, one hundred days out from November?

More on:

Because cooler heads on both sides should begin thinking deeply today about how they will handle not just their immediate post-election rhetoric, but how the results will affect their governance strategies in 2023 and 2024. Whether their parties will benefit in the short term by embracing some of the misinterpretations detailed above is the wrong question. The real question party leaders must wrestle with is what effect their actions, if they are rooted in these misconceptions, will have for the widening and deepening of the chasm that separates the “two Americas,” further extending a downward spiral that poses a potentially existential threat to the American experiment.

Online Store

Online Store