More on:

It seems impossible, but it is true. President Barack Obama was elected to the highest office in the land in 2008 in part because after five years in Iraq, he promised the American people that he would not “do stupid stuff.” He is about to do precisely that in Iraq. It is not just the “I-don’t-know-whether-to-laugh-or-cry” feeling I had when I learned the news that Deputy Assistant Secretary of State Brett McGurk had met with Ahmed Chalabi the week before last to discuss the current crisis and Chalabi’s potential role in a new government. The irony is too much to take, but the dalliance with Chalabi is not actually the issue. Chatting up Chalabi is just a symptom of a bigger, albeit more abstract, problem the Obama and Bush administrations have had in Iraq: Bad assumptions.

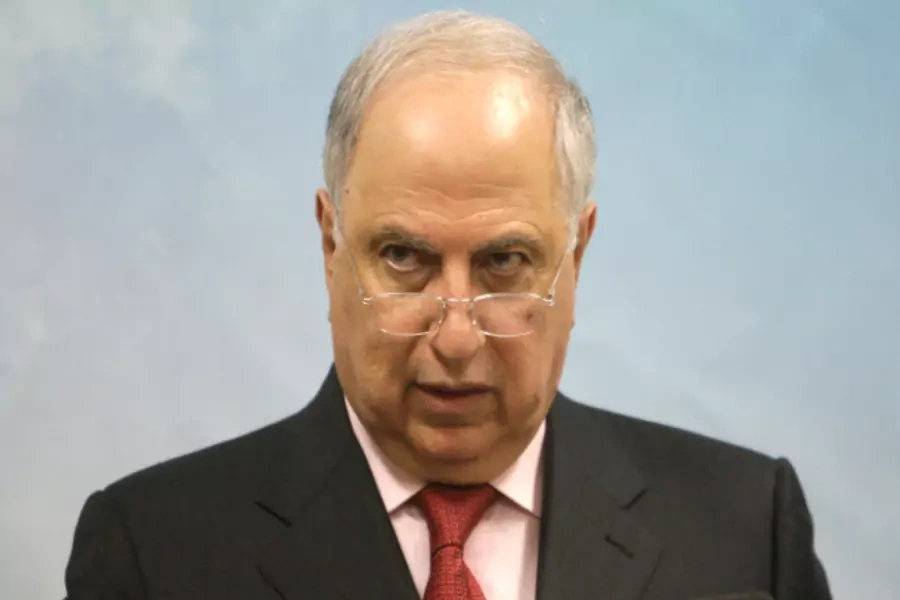

I remember attending a debate at the Brookings Institution in late 2002 about the prospects for an invasion of Iraq. As it turned out it was not much of a debate. The Bush administration was barreling toward war anyway and the panel was stacked. The speakers on the roster that day included Patrick Clawson, Ken Pollack, William Kristol, and Robert Pelletreau. Only Pelletreau, who had served as Assistant Secretary of State for the Near Eastern Affairs and ambassador to Bahrain, Tunisia, and Egypt, warned of the grave consequences of the invasion. Despite his stature, no one much took Pelletreau’s reservations seriously. From the other panelists, the audience got the full cakewalk:

- Iraqis would greet Americans as liberators;

- Resistance would be minimal;

- The occupation of the country would be short;

- Iraq would be able to rebuild itself.

There was precious little discussion of the potential challenges of finding a practical governing formula in a country whose citizens had suffered through so much and who had very different ideas about the future. In a testament to the power of the polemics of the moment, everyone at Brookings that afternoon just assumed that Iraq would become a democracy.

There was no doubt a lot of mendacity that went into Operation Iraqi Freedom, but many of the assumptions about the war and its aftermath were based on naïveté. With rare exception, the supporters of the invasion both inside and outside the Bush administration but did not have a firm grasp of Middle Eastern history, politics, or culture, though they clearly had strong feelings about the region. This is a long way of saying—something which I am sure I have written in any number of other posts—that to have a good foreign policy, you need good assumptions and unfortunately for the untold number of Iraqis who were killed and maimed as well as the 4,486 Americans who lost their lives in combat, in addition to the 32,226 injured, the Bush team went head-long into Iraq with bad assumptions.

The Obama administration is about to make the same mistake. They are operating under a set of assumptions about Iraq that are wrong:

- If leaders in Iraq were more inclusive, “this would not be happening.”

The “this” being the ability of the Islamic State of Iraq and al Sham—which has now renamed itself the Islamic State—to take over large swathes of the country with the help of other militant groups and, importantly, large numbers of Iraqis. It may be true that Maliki’s brand of politics alienated a lot of people, but centralizing power seems to be an iron law of Iraqi politics. If potential leaders like Adel Abdul Mahdi, Ahmed Chalabi, Bayan Jabber, or Ibrahim al Jaafri are going to want to consolidate their power and rule Iraq, they are not likely to choose inclusion no matter how much that makes sense to external observers.

- External forces can make a difference in the fight now underway in Iraq.

My guess is that the administration simultaneously does and does not believe this. Apparently, the White House believes the 300 special forces operators who have been deployed to Iraq can provide enough in the way of coordination, intelligence, and generalized bucking up that Iraqi forces will find it within them to fight. It seems a stretch. If the administration really believed that the United States could make a difference, it would deploy a large number of forces. The reluctance to do that may be a result of politics, of course. It may also be the recognition that the policy prescriptions of the administration’s most vocal opponents would require an occupation of Iraq in perpetuity. Think about that for a moment: A U.S. occupation of a major Middle Eastern country for decades to come. Spare me the comparisons to Korea, Japan, Germany, and the Balkans. They do not work.

- The Islamic State is nothing but an extremist group that will outlive its welcome.

This sounds like a reasonable assumption to make. The first iteration of al Qaeda in Iraq engaged in such a repugnant range of behaviors that it sowed its own demise when the tribes of western Iraq rose up—with the help of money and American arms—against the terrorists. According to endless press reports, the Islamic State is so awful and violent that even al Qaeda central could not countenance the excesses of the group. (The real reason for the split is not Ayman al Zawahiri’s sudden revulsion at the violent methods of Abu Bakr al Baghdadi, but rather competition over who gets to lead the transnational jihadist movement.) As a result, the Islamic State is going to go the same way as its forebearer. There are two problems with this assumption. First, as Thanassis Cambanis makes clear in an interesting article in Sunday’s Boston Globe, the Islamic State actually has something to offer the Sunnis now under its flag—a semblance of citizenship that is impossible in Iraq and elsewhere in the region. Second, this is not 2006. As the Turks say, “You can’t bathe in the same bath water twice.” The “awakening” that eventually disposed of al Qaeda in Iraq and other groups that terrorized the country from 2004-2007 happened simultaneously with (or almost simultaneously with) the surge of American forces, which is not happening again.

- Iraq makes sense

There are, no doubt, many people who believe themselves to be Iraqi, but the events of the last decade have brought the ungainly beast that is Iraq into sharp relief. It is the amalgamation of three Ottoman provinces that Colonel Arnold Wilson—the British High Commissioner in Mesopotamia from 1918-1920—dreamed up because a central administrative unit governed from Baghdad would better serve London’s interests in the area. The violence that has plagued the country since the American invasion—which has produced demographic shifts—the surreal politics, and the heightened ethnic and sectarian tensions it has produced do not bode well for the country’s future. As I wrote a few weeks ago, Iraq no longer makes sense to the people who live there. The Kurds want to pull away, the tribes of Anbar do not like being ruled from Baghdad, and in the south, the people in Basra, for example, believe that they could do better without the rest of the country. Unity has become a fiction to many, especially to the Kurds who never felt much a part of Iraq anyway. It is, of course, possible that different groups will unite against the Islamic State and its Baathist allies of the moment, but that does not in and of itself strengthen the assumption that people still accept the idea of Iraq.

After all that has happened in the last three weeks, it is still hard to know what the administration wants in Iraq. Other than the end of Maliki and the defeat of the Islamic State, what is Washington’s goal? The assumptions underlying the White House’s tactical approach to the problems that Iraq now presents do not line up with reality. Both are rather worrying. Without good assumptions and a clear objective based on those assumptions, the United States risks getting stuck in the maelstrom that is now Iraq. Allah have mercy…

More on:

Online Store

Online Store