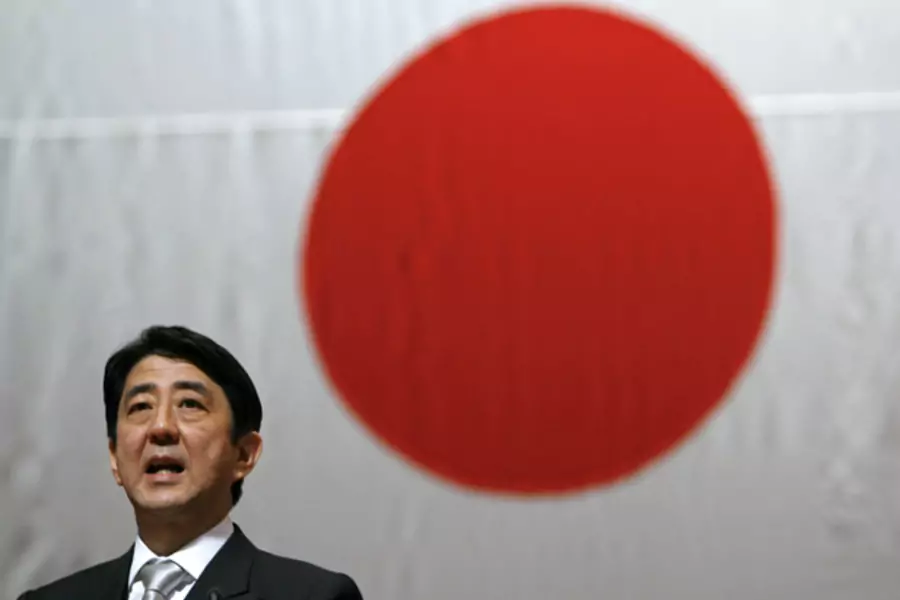

Hello (Welcome Back), Shinzo Abe: Prime Minister of Japan

If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again. That old saying could be the motto of Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe, who today marks the end of his third month in office. You see, he had this job once before. On September 26, 2006, he was sworn in as Japan’s ninetieth prime minister, the youngest ever and the first born after the end of World War II. Abe’s initial tenure was mired in missteps and scandals, however, and just 351 days after taking the oath of office he resigned. He remained active in politics, though, as Japan ran through five more prime ministers in five years. Last September he launched his comeback. He first won control of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in a hotly contested battle. Then in December, he led the LDP to a landslide victory over the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), which three years earlier had broken the LDP’s stranglehold on Japanese politics. Abe certainly doesn’t lack for challenges the second time around, what with Japan’s economy continuing to stagnate and China seeking to establish itself as the dominant power in Asia. Whether he can master these challenges will determine whether he redeems his reputation—or confirms it.

The Basics:

Name: Shinzo Abe

More on:

Date of Birth: September 21, 1954

Place of Birth: Nagato, Yamaguchi

Religion: Shinto

Political Party: Liberal Democratic Party (LDP)

Marital Status: Married to Akie Abe (born Akie Matsuzaki) since 1987

More on:

Children: None

Alma Mater: Seikei University, University of Southern California

Political Offices Held: Member of Parliament (1993-), Chief Cabinet Secretary (2005-2006), Prime Minister (2006-2007, 2012-)

What supporters say. One of the reasons that Abe lasted just a year as prime minister his first time around was the perception that he didn’t do enough to tackle Japan’s formidable economic problems. The economy remains the top issue for most Japanese. It’s why ninety-year-old Masao Ibuki voted for the LDP in December:

I’m really worried about the economy. I hope the LDP will work on that first

Abe looks to have learned his lesson. He has put the economy front and center his second time around. Norihiko Narita, a political scientist at Surugadai University, says:

Mr. Abe has clearly learned the lessons of his past failure. And the biggest lesson is that voters care more about the economy.

So we now have “Abenomics.” It features stimulus spending, easy monetary policy, and structural reforms. Abe’s goal is to reverse two decades of flagging growth, high government debt, and deep public skepticism about business and government leaders.

How has Abenomics fared so far? Pretty well, actually. Michael J. Green, one of America’s most astute Asia experts, writes:

Thus far it has worked. The markets and business confidence are up.

The New York Times concurs:

Mr. Abe’s promises of economic revival have already created a budding optimism in urban areas like Tokyo, where the stock market has rallied and restaurants seem more crowded than they were during years in which many people resigned themselves to Japan’s fading prospects. The new, if fragile, hopefulness has been boosted by rising corporate profits, as a weakening yen has brought desperately needed relief to badly shaken electronics corporations and other exporters struggling to compete with Chinese and Korean rivals.

Trade looks to be one area where Abe hopes to shake things up. He recently announced that Japan will join the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), trade negotiations that involve the United States and ten other countries. TPP seeks to create free trade among Pacific countries. Unlike neighboring South Korea, Japan has generally shied away from striking free-trade deals with its major trade partners. Signing on to the TPP could boost the Japanese economy by $33 billion. That sounds like a big number, but it’s less than one percent of Japan’s overall economic output.

Noah Smith, a professor at Stony Brook University, thinks that TPP could be essential to Abe’s success:

Increased trade is probably Japan’s best bet in getting out of its current economic doldrums. If Abe can actually push this through, this will be his economic legacy, and it will be a positive legacy.

Japanese regulations and trade barriers have long been a headache for foreign businesses. The U.S. trade deficit with Japan grew 21 percent last year, reaching $76.3 billion. Japan has high tariffs on rice and beef, and Tokyo has made it virtually impossible for U.S. car manufacturers to penetrate its markets.

Trade barriers annoy some Japanese as well. Shigeaki Okamoto, a farmer in Aichi prefecture, can’t sell his rice to China because a company holds a monopoly on rice exports. “Japan,” he fumed to the New York Times, “is wrapped in an invisible web that prevents you from showing any sort of initiative.”

So far the Japanese public is giving Abe thumbs up; his approval ratings now stand around 70 percent. Abe even seems to be winning support for his tough talk on foreign policy, something that wasn’t the case during his first stint as prime minister. Japanese worry now about what a rising China means for them. Time writes:

If the Japanese seem uniformly passionate about anything, it’s antipathy toward a rising neighbor to the west. More than 80 percent of Japanese say they harbor unfriendly sentiments about China, up nearly 10 percent from last year, according to a survey by Japan’s Cabinet Office.

Naomi Mabashi voted for the LDP with China in mind. As Japan is increasingly threatened by its rising neighbor, Mabashi found Abe’s vow to improve the relations with the United States appealing:

For years, more and more Chinese military aircraft have come very close to Japanese territory… China’s power is growing, and I want Japan and the U.S. to have a good relationship.

Yoshiko Sakurai, a Japanese journalist who has long advocated taking a hardline stance on China, tells Time:

Ten years ago, I was considered an ultra-nationalist. But now these are ordinary thoughts in Japan.

With Tokyo and Beijing locked in a standoff over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, most Japanese aren’t complaining that Abe has moved to increase Japan’s defense spending for the first time in over a decade. "We need to thank China,” retired SDF general Toshiyuki Shikata says, “for awakening the Japanese people to the need for a normal military force.”

What critics say. Nationalist sentiment is rising in Japan, but Abe is probably still further to the right than the average Japanese voter. That means that a foreign policy misstep could tank his public approval ratings. Aiji Tanaka, a political science professor at Tokyo’s Waseda University, told Bloomberg:

Abe’s popularity will disappear very quickly if he does something wishy-washy or overreacts and leads Japan into a real crisis with China. If he is calm and handles the situation well, he can keep up the momentum until July.

July is critical because that is when Japan’s elections for its upper house take place. If Abe’s LDP colleagues fare well in the elections, he might be tempted to push hard on the foreign policy front. Andrew L. Oros, an East Asia scholar at Washington College in Maryland, tells the New York Times:

In his first six weeks, he has done everything he can to show he is a moderate. But after July, he might feel he has a freer rein to do things that he thinks are justified.

The Economist thinks that Abe isn’t very good when it comes to history:

He appears to think that Japan did very little bad in the imperial years before its utter defeat in 1945 (a view that riles Japan’s neighbours). Even weirder, Mr Abe writes as if Japan has done little good in the years since. He writes of freeing “the country called Japan” from “the grip of post-war history.”

Not surprisingly, Beijing isn’t applauding Abe’s nationalist rhetoric. Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Hong Lei complained:

It is rare that a country’s leader brazenly distorts facts, attacks its neighbor and instigates antagonism between regional countries.

Ouch. Japanese analysts warn that escalation is not in Japan’s interest or within its capabilities. Narushige Michishita, a professor at Tokyo’s National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies, explains:

The fact that defense spending will increase is important for symbolic reasons, but it doesn’t mean much in terms of a real increase in defense capabilities. Realistically, China’s defense budget is growing so rapidly, there’s no way we can compete with that.

Abe’s support for nuclear power is a source of public discontent, especially with the 2011 Fukushima disaster so fresh in the public memory. A forty-three year old mother from Tokyo who voted against the LDP said:

I have children and I have to think about their future.

Polls after the December election showed that 14 percent of voters wanted to put an immediate end to nuclear power use, and 64 percent wanted to phase it out over time. But Abe announced within days of taking office that he would reconsider his predecessor’s plan for reducing Japan’s dependence on nuclear energy.

Abenomics could also create some problems for its namesake. Henny Sender argues in the Financial Times that Abenomics will not achieve its goals:

These policies will lead to rising rates without offsetting benefits, given the lack of structural reform, adverse demographics, low productivity and the competitive threat from neighbours in China and Korea.

Former Japanese vice finance minister Eisuke Sakakibara told CNBC that he worried about Abenomics meeting its inflation goals:

In terms of two percent inflation, it will fail. Deflation is structural. Even at the time, when Japan was in the upward [growth] swing between 2002 and 2007, prices went down. It will be extremely difficult to get out of deflation.

The New York Times reports that Abe’s push to devalue the yen might not pay off. Why? It could trigger a currency war that leaves Japan no better off than it is today, and perhaps even worse off. Beijing has already begun to bang the table at Abe’s currency moves, no doubt because in making Japanese exports more competitive, he is making Chinese exports less competitive.

Then there is the problem of Japan’s national debt. Washington is a miser compared to Tokyo. Japan’s national debt now exceeds 200 percent of its GDP. The Economist warns Abe not to:

return to the big-spending days of past LDP governments, which were addicted to construction and public works.

Abe apparently does not take advice from the Economist. He is pushing a massive, decade-long stimulus centered on public works. Just how massive? It will cost about $2.4 trillion. Yes, trillion. That amounts to 40 percent of Japan’s GDP.

Other critics worry about Japan joining the TPP. Japan’s tariffs on imported rice reach up to 777.7 percent. That’s a sweet deal if you are a Japanese rice farmer worried about foreign competition. Not surprisingly, that means almost all Japanese rice farmers oppose the TPP. So a deal could cost Abe their support. Some Japanese critics of TPP also fear that lowering trade barriers would damage Japan’s social fabric. Hisaharu Ito, an official in the Union of Agricultural Cooperatives in Aichi Prefecture, worries:

The T.P.P. is a battle over what kind of country we want Japan to be... Do we want to turn into a harsh society of winners and losers, or remain a gentler society where benefits are shared?

As a wise man from Cambridge once said, all politics is local.

Stories you will hear more about. Now that Abe has returned to the prime minister’s office, each of East Asia’s powers is headed by someone from a veteran political family. North Korea’s Kim Jong Un is the son and grandson of dictators, South Korea’s Park Geun-hye is the daughter of a military dictator, and China’s Xi Jinping is the son of a hero of the Chinese Revolution. As for Abe? His father, Shintaro Abe was a foreign minister and his maternal grandfather, Nobusuke Kishi, was prime minister from 1957-1960. Abe prayed at their graves after the LDP’s victory in December.

Abe’s family lineage is seldom mentioned in the U.S. press. In Asia, however, it is news. To many people in northeast Asia, his grandfather symbolizes Japan’s unwillingness to let go of its imperial past. Kishi was a senior official in Japanese-occupied Manchuria, and he was a member of the cabinet that took Japan into war against the United States in 1941. He was arrested for war crimes once the war ended. The occupying U.S. authorities never tried him on the charges, and he was released after about three years.

Abe says his grandfather is his role model and the inspiration for his desire to “change the post-war regime.” To fulfill that goal, Abe has packed his cabinet with ideological allies. The Economist summarizes:

Fourteen in the cabinet belong to the League for Going to Worship Together at Yasukuni, a controversial Tokyo shrine that honours leaders executed for war crimes. Thirteen support Nihon Kaigi, a nationalist think-tank that advocates a return to “traditional values” and rejects Japan’s "apology diplomacy" for its wartime misdeeds. Nine belong to a parliamentary association that wants the teaching of history in schools to give a better gloss to Japan’s militarist era….To describe the new government as "conservative" hardly captures its true character. This is a cabinet of radical nationalists.

Abe has expressed regret for not visiting Yasukuni during his first stint as prime minister. His decision to stay away displeased Japanese nationalists. How displeased? Well, one nationalist cut off one of his fingers and mailed it to the LDP in an effort to shame Abe into going. The upside to staying away from Yasukuni is that it helped Abe enjoy relative success with his regional diplomacy. A visit to the shrine now will almost certainly inflame anti-Japanese sentiment in China and South Korea.

If the Kishi legacy hurts Abe in neighboring countries, his wife, Akie Abe, helps him at home. She has unprecedented visibility in a country where women in her position are expected to be oku-sama, or subordinate wives who are seen and not heard. During Shinzo Abe’s last term as prime minister, Newsweek quipped:

In previous eras, the main job of a political wife was to look pleasant and stay a respectful three steps behind her man. Trying out new flower arrangements was as edgy as it got. But Akie Abe is cut from a whole new cloth. She’s got something to say and she’s not afraid to say it--whether in a foreign language, in her own refined Japanese or on her blog.

During Abe’s first stint as prime minister, he and Akie came third in a survey that asked Japanese to rank “ideal couples.” In Seoul, she charmed the local press by reciting a poem in Korean. After her husband resigned in 2007, she opened a bar in Tokyo specializing in the cuisine of her husband’s home district.

Akie says that she keeps a close eye on her husband’s health problems, which played a role in his 2007 resignation. She says she will be:

watching him because he will come under a different sort of stress now that he is prime minister.

Abe suffers from ulcerative colitis, a condition he initially hid from the Japanese public. It’s a painful, and for many of its sufferers, embarrassing condition. But Akie now sees a benefit to her husband acknowledging his illness:

Once he made it public, though, many patients with the same disease thanked him for being an encouragement to them.

Abe has something in common with Egyptian president Mohammed Morsi: both men did graduate work at the University of Southern California in the late 1970s. So they can always chitchat during the slow moments at summits about the Trojans’ past gridiron glories. Abe is not the first Japanese prime minister to have studied at USC, though. That distinction belongs to Takeo Miki, Japan’s forty-first prime minister, who attended USC back in the 1930s.

In his own words. Abe has not dwelled on the failures of his first try as prime minister. In an article that he wrote before last December’s election, he turned his lemon into lemonade:

I have experienced failure as a politician and for that very reason, I am ready to give everything for Japan.

As to his country’s future (and as a rebuke to Richard Armitage, who co-authored a paper that implied otherwise), Abe declared:

Japan is not and will never be a tier-two country.

A fear of Japan’s decline preoccupies Abe. He made the case for joining the TPP in alarmist terms:

Japan must remain at the center of the Asian-Pacific century. If Japan alone continues to look inward, we will have no hope for growth. This is our last chance. If we don’t seize it, Japan will be left out.

Abe is a nationalist. And like many Japanese nationalists, he spends a lot of time claiming that Japan’s past misdeeds aren’t really misdeeds. In a speech earlier this month, he said that the twenty-eight Japanese officials tried as Class-A war criminals after the end of World War II were “not war criminals under the laws of Japan.” As for the war itself, he stated:

The view of that great war was not formed by the Japanese themselves, but rather by the victorious Allies, and it is by their judgment only that [Japanese] were condemned.

In an interview in December, he said that he wanted to revise Japan’s 1995 apology for its actions during World War II:

I want to make a statement that is forward-facing and appropriate for the 21st century.

What he comes up with isn’t likely to please Japan’s neighbors. He has made a hash out of Japan’s continued failure to apologize for the use of Chinese and Korean “comfort women” (a euphemism for sex slaves) during World War II. Abe has shied away from the comfort women story in recent weeks, but his 2007 comments denying that the women were forced into sexual slavery sparked great controversy.

Despite these tensions, Abe maintains that:

ties between Japan and Korea is [sic] something that cannot be severed.

Don’t be too sure about that. Nationalism is a powerful force, both inside and outside Japan.

Foreign Policy. Abe’s top foreign policy priority is to counter a rising China. He recently warned with respect to the confrontation over the Senkaku Islands:

increasingly, the South China Sea seems set to become a “Lake Beijing,” which analysts say will be to China what the Sea of Okhotsk was to Soviet Russia: a sea deep enough for the People’s Liberation Army’s navy to base their nuclear-powered attack submarines, capable of launching missiles with nuclear warheads. Soon, the PLA Navy’s newly built aircraft carrier will be a common sight—more than sufficient to scare China’s neighbors.

In contrast, he sees Japan as a leader and policeman in East Asia:

When the Asia-Pacific or the Indo-Pacific region gets more and more prosperous, Japan must remain a leading promoter of rules. By rules, I mean those for the—for trade, investment, intellectual properties, labor, environment, and the like.

To maintain Japan’s position, Abe is looking to make friends with countries in Asia not named China. He hopes that India will return the favor. Back in 2007, he told the Indian parliament that Japan and India were made to be allies:

A “Broader Asia” that broke away geographical boundaries is now beginning to take on a distinct form. Our two countries have the ability—and the responsibility—to ensure that it broadens yet further and to nurture and enrich these seas to become seas of clearest transparence... This partnership is an association in which we share fundamental values such as freedom, democracy, and the respect for basic human rights as well as strategic interests...The Strategic Global Partnership of Japan and India is pivotal for such pursuits to be successful.

This "Broader Asia" would make up a part of what Abe calls his “strategic diamond,” a proposed four-member alliance that would also include Australia and the United States. Abe’s deputy prime minister and finance minister Taro Aso speaks of supporting democracies within an “arc of freedom and prosperity” stretching as far west as Eastern Europe.

Beijing certainly recognizes the point of Abe’s strategy, which is perhaps why it has been taken such a confrontational stance over the Senkaku Islands, which the Chinese call the Diaoyu Islands. With a lot at stake, Abe has upped the ante. He has likened the Senkaku dispute to an island conflict in a different part of the world:

Looking back at the Falkland Islands conflict, former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher said the following: “The rule of international law must triumph over exertion of force.”

Japan, which currently has administrative control over the Senkakus, has denied any territorial dispute over the islands, claiming that international law stands in its favor:

History and international law both attest that the islands are Japan’s sovereign territory. After all, for the long period between 1895 and 1971, no challenge was made by anyone against the Japanese sovereignty. We simply cannot tolerate any challenge now and in the future. No nation should make any miscalculation about [the] firmness of our resolve.

Despite this tough talk, Abe added that he hopes to avoid conflict with China:

At the same time I have absolutely no intention to climb up the escalation ladder. For me, Japan’s relations with China stand out as most—as among the most important. I have never ceased to pursue what I hold [is a] mutually beneficial relationship based on common strategic interests, with China. The doors are always open on my side for the Chinese leaders.

Abe has said that Japan wants to make:

the seas, which are the foundation of our nation’s existence, completely open, free and peaceful.

The Senkakus aren’t the only group of relatively inconsequential islands that will occupy Abe’s attention. An even smaller group of rocky islands, Takeshima (known as Dokdo in South Korea) is causing tension between Japan and South Korea. Seoul controls these rocks, but Tokyo also claims them in hope of maintaining rights to nearby fisheries.

Outlook for Relations with Washington. Abe credits Japan’s improving relations with the United States to his own return to office. After meeting with President Obama in February, Abe declared:

We have restored the bonds of friendship and the trust between Japan and the United States that had been markedly damaged over the past three years.

The Economist observes, however, that there was little to improve; U.S.-Japanese relations continued just fine when the Democratic Party of Japan, which Abe’s LDP ousted last year, was in power.

Abe sees the alliance between the United States and Japan as a pillar of Japanese regional and global prosperity:

as your long-standing ally and partner, Japan is a country that has benefited from and contributed to peace and prosperity in the Asia-Pacific for well over half a century. The bedrock for that, needless to say, has been our alliance.

In turn, Abe sees Tokyo’s relationship with Washington as an essential component of the U.S. rebalancing toward Asia:

In a period of American strategic rebalancing toward the Asia-Pacific region, the US needs Japan as much as Japan needs the US. Immediately after Japan’s earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disaster in 2011, the US military provided for Japan the largest peacetime humanitarian relief operation ever mounted – powerful evidence that the 60-year bond that the treaty allies have nurtured is real. Deprived of its time-honored ties with America, Japan could play only a reduced regional and global role.

Does Washington see its relationship with Tokyo in the same light? Perhaps. But U.S. and Japanese priorities don’t always align. The Obama administration is not eager to get pulled into a conflict over the Senkaku Islands. One anonymous U.S. official told the Washington Post:

I’m pretty frank with people: I don’t think that we’d allow the U.S. to get dragged into a conflict over fish or over a rock… Having allies that we have defense treaties with, not allowing them to drag us into a situation over a rock dispute, is something I think we’re pretty all well-aligned on.

The U.S. military bases in Okinawa have been an irritant in U.S.-Japanese relations since the United States returned control of Okinawa to Japan in 1972. (Would you want a foreign military base smack dab in the middle of your town?) Abe has said that the base is “imposing large burdens on the people of Okinawa.” Occasional misconduct by American soldiers hasn’t helped things. And just last week, North Korea threatened to attack U.S. bases in the Pacific, including Okinawa. Despite these political headwinds, Abe announced on Friday that he would ask for a permit to begin construction of a new American base in a different part of Okinawa. The problem is that Okinawans don’t just want the base moved; they want it gone completely.

Washington welcomed Japan’s decision to join the TPP. Japan is the world’s third largest economy, so its involvement makes TPP an even bigger deal than it already was. The news wasn’t well received in Beijing, which worries that TPP could give the United States additional influence in Asia. China recently announced the opening of talks to create a free trade agreement between China, Japan, and South Korea.

Abe is likely to avoid any major foreign policy moves until after the July elections for Japan’s upper house. But while he had pledged to make the economy job number one, foreign policy could yet be the issue that defines his prime ministership.

For more on Shinzo Abe and Japan, check out the CFR blog Asia Unbound, especially the Is Japan in Decline? series of posts.

Online Store

Online Store