Guest Post: U.S. Interest in Tunisia’s Successful Democratic Transition

Brian Garrett-Glaser is an intern in the Center for Preventive Action at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Tunisia’s transition to inclusive democracy is not a fait accompli. Despite holding successful 2014 elections and recently receiving a “free” rating for political rights and civil liberties from Freedom House, the small North African nation is struggling with significant economic and security challenges as well as eroding popular support for democratic reforms. The Jasmine Revolution, which ousted Tunisian dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in early 2011 and sparked a wave of protests across the Middle East, was as much a call for better economic conditions and stability as democracy and human rights. Yet, absent the expansion of economic opportunities and improved security, democratic reforms in Tunisia will not satiate the previous demands for change.

On March 5, the United States announced a number of laudable economic partnership programs to assist with Tunisia’s reforms. U.S. secretary of commerce Penny Pritzker said that it is “in the United States’ strategic interest” to see Tunisia’s government succeed—and she is spot-on for multiple reasons. Tunisia is a relative island of stability in a chaotic region, and the outcome of its democratic transition—as well as the role played by the United States throughout—will have a significant impact on regional and global security, U.S.-led efforts to counter violent extremism, and perceived credibility of U.S. actions in the Middle East.

Coinciding with this announcement, Pritzker led a delegation to Tunisia to encourage the government to enact much-needed economic reforms. But there is more to be done. The Obama administration’s FY2015 budget request placed Tunisia as the ninth largest recipient of bilateral aid in the region—the same level of aid given in 2010 prior to the revolution. In the long run, economic partnerships between the two nations will likely have a broader impact than solely supporting Tunisia’s economy.

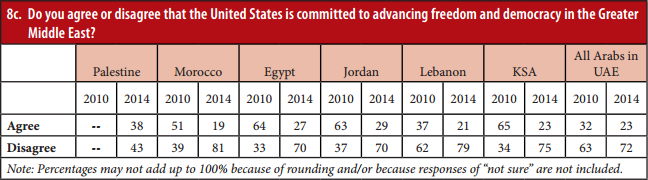

Beyond providing aid, the United States has a role to play in ensuring Tunisia’s transition to democracy, given that a stable Tunisia could strengthen U.S. security interests abroad, support efforts to counter violent extremism, and serve as a model of good governance based on both democracy and Islam. Thus far, U.S. policy in reaction to the Arab Spring has negatively impacted its image and perceptions of its commitment to democracy throughout the Middle East. A 2014 poll conducted by the Arab American Institute concluded that Arabs judge the Obama Administration as least effective in “improving relations with the Arab/Muslim Worlds,” resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and “dealing with transformations brought on by the ‘Arab Spring.’” The poll also found that there was a “sharp decline in confidence that the United States is committed to democracy across the Middle East” between 2010 and 2014.

Source: “Five Years After The Cairo Speech: How Arabs View President Obama and America,” Zogby Research Services, LLC, June 2014, p 16.

Moreover, snapshots of public opinion demonstrate Tunisians’ declining interest in democracy and a burgeoning readiness to accept improvements in economic opportunity and stability from a strongman at the cost of democratic institutions and respect for human rights. A 2014 Pew poll found that 40 percent of Tunisians preferred good democracy over a strong economy in 2012 and just 25 percent felt the same in 2014. The poll also asked if they should rely on a “democratic form of government” or a “leader with a strong hand” to solve their country’s problems. In 2012, 61 percent answered a democratic form and only 37 percent a leader with a strong hand; by 2014, these numbers had flipped, with 59 percent calling for a leader with a strong hand and only 38 percent preferring a democratic form of government. A loss of interest in pursuing a transition to democracy could have negative implications for U.S. political and security interests in the region.

If Tunisia does backslide to authoritarianism, similar to the path Egypt has taken, then the United States will suffer a blow to its security interests abroad and at home. As Mara Revkin argued in a 2014 Foreign Affairs article, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s rise to power proved to be a major victory for al-Qaeda. When the Egyptian military outlawed the Muslim Brotherhood and violently suppressed all forms of protest, al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahri attributed the group’s failure to its abandonment of violence in favor of political participation and subsequently called for jihad against the Egyptian state. Since President Mohamed Morsi’s ouster in July 2013, there has been a sharp uptick in terrorism within Egypt’s borders—especially in the troubled Sinai Peninsula, which is now claimed by Ansar Beit al-Maqdis, a group that has recently pledged allegiance the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Sisi may be a strong military ally in the “War on Terror,” but his policy of blanket repression toward Islamists is counterproductive. A democratic Tunisia, on the other hand, could prove an ideological counterweight to help neutralize extremism through inclusive politics and the promotion of moderate Islam.

Tunisia’s budding democracy provides an opportunity to dispel skepticism surrounding the role of Islam in a participatory government. The 2014 Tunisian constitution—ratified with the support of over 90 percent of the legislature—has been praised by many observers as one of the most progressive in the Muslim world. Nidaa Tounes, the largest secular party, rejects the ultra-secularist French concept of laïcité, and al-Nahda, Tunisia’s dominant Islamist voice, does not support using the law to impose religion. The same Pew poll mentioned earlier found that Tunisians who pray five times per day are more likely to think democracy is preferable to other forms of government. Tunisian attitudes toward democracy and Islam prove that the two are not incompatible, and it is in the United States’ strategic interest for this realization to spread throughout the region.

As the United States assists Tunisia in building a robust economy, it is seizing an opportunity to strengthen voices of a more moderate Islam, build trust with new governments, and rehabilitate the U.S. image in the region. There is no doubt that U.S. resources in the Middle East are stretched thin, but the Obama administration’s emphasis on Tunisia will prove to be a smart long-term strategic investment, with the potential for vast benefits for security, democratization, and efforts to counter violent extremism.

Online Store

Online Store