Egypt: Anchors Away

More on:

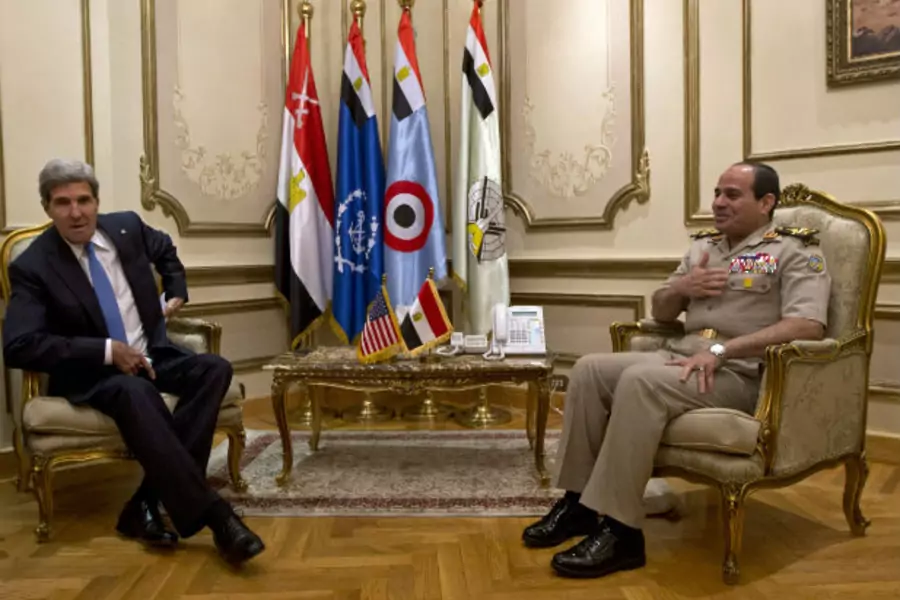

Over the last week or so, there have been more than a few stinging indictments of U.S.-Middle East policy. Whether it is Iran’s nuclear program, the civil war in Syria, or Secretary of State John Kerry’s effort to push Israeli-Palestinian peace talks, the Obama administration is near universally derided as both timorous and out-classed in the face of formidable adversaries. It’s been an impressive pile-on even if some of this commentary is actually more about politics than analysis. Among the various op-eds, columns, and articles, two caught my attention. On November 8 in his regular column for Foreign Policy, James Traub skewered the White House for failing to talk tough to the Egyptian military about its blatantly un-democratic approach to post-Morsi Egypt. A few days later, the Washington Post’s deputy editorial page editor, Jackson Diehl, published a stem-winder of a column that ripped Kerry on every important issue in the Middle East, including the Secretary’s apparent willingness to accommodate what is shaping up to be Egypt’s non-democratic transition.

Traub and Diehl are serious and accomplished observers of American foreign policy and their contributions to the recent foreign policy debate are not politically motivated. Yet the assumption underlying their articles that the United States can be an anchor of reform in Egypt—a view that is shared among a diverse and influential subset of the American foreign policy elite—is suspect. Before I am accused of being a troglodyte, let me be clear: Democracy in Egypt would be a very good development, providing Egyptians with the representative government they have long sought. I have also written that Washington’s approach to Egypt over the last three years should have emphasized principles like personal freedom, non-violence, transparency, and equal application of the law. That said, it strikes me as odd—given the available evidence—that analysts believe democracy promotion, whether in the form of actual programs designed to encourage more open and just societies or rhetorical support for progressive change, would make an appreciable difference in Egypt.

My skepticism is a function of the fact that for Egyptians, the stakes are so high in their struggle to define new political and social institutions, there is very little that external powers can say or do to influence the way in which sons and daughters of the Nile calculate what is best for Egypt. It is also based on my sneaking suspicion that in the end, the people who were central to making the January 25 and June 30 uprisings happen will not determine the trajectory of Egyptian politics. Instead, the contours of Egypt’s new political order will likely be determined in a war of position among the military, intelligence services, police, and the counterrevolutionaries embedded in the bureaucracy. Needless to say, this is not a propitious environment in which America’s limited resources can make much of a difference.

There is a larger issue than the particulars of the current Egyptian political environment, however. There have been reams and reams written about how and why democracies emerge. Within the academic literature, there are essentially two different schools of thought. The first emphasizes “prerequisites” for democracy—for example, the emergence of a middle class; a certain level of economic development; national unity; and political culture. The second focuses on the calculations of elites. This so-called rationalist approach posits that transitions to democracy occur when political circumstances alter the incentives and constraints of a prevailing elite seeking to survive. This is the way that leaders who have no particular commitment to democratic ideals become democrats. I am simplifying, of course, and the work on transition to democracy is rich, but much of it is built on these two schools of thought.

Now, back to Egypt. If we take the two primary conceptions of how democracy emerges seriously, what can the United States reasonably do? Among prerequisites for democracy, it seems that, in the abstract, the United States can actually do something about wealth. The United States still occupies the most influential position in the global economy, calls the shots at international financial institutions like the IMF, and holds significant economic influence in Europe and Asia. Yet for all that power and prestige, America’s global economic influence seems to be eroding due to the rise of others and Washington’s dysfunctional politics. The combination of the two makes it difficult to marshal support both at home and abroad to help Egypt economically. Yet Washington is only half the problem. Egyptian politics and the country’s recent instability compromise the efficacy of outside assistance.

If the United States has little capacity to encourage the development of what some believe to be prerequisites for democracy, its ability to shape the calculations of its leaders is also quite limited. What incentive can Washington offer that will alter the interests and constraints of Egypt’s leaders? It’s unlikely that even if the United States had the resources and political will to offer, for example, billions of aid in exchange for democratic change that Major General Abdel Fatah al Sisi would respond positively. As noted above, under circumstances in which Egyptians believe they are in an existential struggle for the soul of the country, outsiders—any outsiders—will have very little influence to compel the leaders to do something they would not otherwise do. For all the money that the Saudis, Emiratis, and Kuwaitis are providing, they are merely helping to enable what the Egyptian armed forces would have done anyway.

There may be other examples, but I can only think of one instance in which an outside power had a decisive influence on the direction of politics in a country: the EU and Turkey. The prospect of membership in the European Union altered the incentives of Turkish Islamists and placed constraints on Turkey’s senior military officers in ways that made the wide-ranging democratic reforms (which have turned out to be reversible) of 2003-2004 possible. The Turkish relationship with the EU is unique, however. As long as there seemed to be a credible chance for Turks to become members of Europe, Brussels had a dynamic effect on Turkish politics. The United States, in contrast, is not going to offer Egypt membership in its own exclusive club.

In a world that some imagine, the United States has the moral, political, and financial authority to promote democratic change in countries thousands of miles away from its shores. I suppose this is the burden of having made “the world safe for democracy”—even though we really did not—and facing down fascism as well as communism. Given this history, I can understand why it is difficult to accept the fact that the traditional tools of American diplomacy do not actually matter much in the struggle for Egypt. We should get used to it.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store