Do foreign holdings of US debt put the US economy at risk?

More on:

I am testifying later today (gulp) before the House budget committee -- and the time that normally goes into writing blog posts has gone into preparing my written testimony.

That means I haven't had time to fully explore a range of interesting topics:

- The Economist's (continued) insistence that a 10% of GDP (and rising) current account surplus, 30% y/y export growth and $500b in intervention in the fx market is not a sign that a currency is (just perhaps) a wee bit undervalued.

- Larry Summers' argument that the preeminent economic policy challenge right now is to find ways to address the unequal distribution of the gains from recent growth. No doubt his new paper with Jason Furman and Jason Bordoff is worth reading.

- Bear Stearns' decision to back -- i.e. to provide a loan that, best I can tell, allows the fund's existing creditors off the hook -- the least troubled of its two troubled hedge funds but not to back the other, more leveraged and thus more troubled, fund. Like Naked Capitalism, I wonder if that is viable -- from the outside, Bear seems to be threatening to turn over the keys of its more troubled fund to that funds' creditors and daring them to liquidate the more leveraged funds assets and set a market price that would make it hard to mark-to-model, no matter what the consequences are for Bear's reputation. If I am reading this wrong, do tell ...

The Budget Committee's hearing is structured around the question of whether large foreign holdings of US debt put the US economy at risk? My answer is pretty simple: the United States' ongoing need for a large increase in foreigners' willingness to hold US assets in order to fund large ongoing deficits remains a potential economic vulnerability.

I try to lay out two different risks. One is that foreign investors fail to provide the US with enough financing, forcing too rapid adjustment. The other is that foreign investors provide the US with so much financing -- at least in the short-term -- that they prevent a necessary adjustment from happening, allowing the underlying disequilibrium to build.

I know my comparative advantage -- I'll be focusing on the US debt that foreign central banks hold as part of their reserves. The actions of central banks -- and sovereign wealth funds -- are central to both stories.

As Ted Truman and Fred Bergsten have argued, what matters most for the US -- as for any country with a large deficit -- is the total amount of financing that foreign investors are willing to provide, not the precise financial instruments that foreign investors want to hold. If total inflows are less than the current account deficit, something has to change -- the dollar has to fall and interest rates have to rise to the point where foreigners are willing to lend and invest more, or the US would need to borrow and invest less.

But so long as central banks offset any fall off in private financing, this specific risk won't materialize. That seems -- at least to me -- what has happened over the past few quarters.

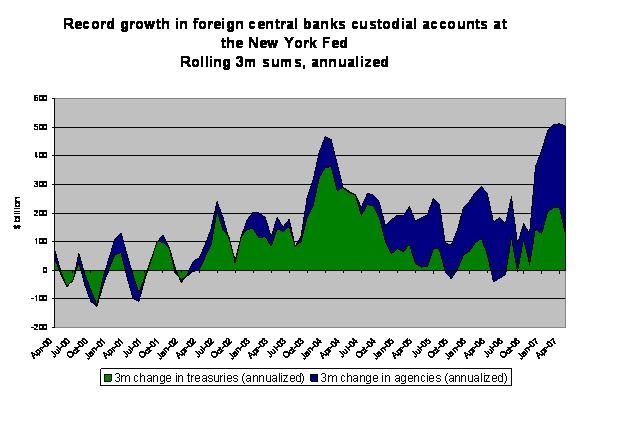

There isn't a great high frequency measure of central bank financing of the US, but the recent growth in the FRBNY's custodial claims is certainly suggestive. I plotted the rolling three month sum change (annualized, so the change over any three month period is multiplied by four) -- the resulting picture pretty much tells the story. Central banks have upped their financing of the US significantly over the past few months.

This graph doesn't include the data for June. The June data will - barring a huge increase in custodial holdings this week -- show something of a fall-off in the pace of growth in custodial holdings.

However, the change in the NY Fed's custodial accounts aren't entirely determinative. Central banks don't hold all their reserves at the New York Fed. I actually think total central bank financing of the US has been running closer to $800b annual pace than to the $500b annual pace implied by the custodial accounts alone. Total central bank demand for US assets may have fallen a bit in June, but I suspect some of the flows that showed up in the New York Fed's custodial data earlier this year will show up elsewhere in June. That is just a hunch though.

What is relatively clear is that the large increase in central bank financing of the US since last fall -- other indicators tell a similar story to the Fed's custodial data -- has allowed the US to weather a fairly significant slowdown in private capital flows. When the US economy slowed and the global economy did not, private investors understandably became less willing to finance the US.

But the large increase in central bank purchases raises another risk: central banks may be thwarting all adjustment, not just thwarting disruptive adjustment.

Providing the US with enough financing to avoid any adjustment avoids problems in the near-term, but it is also allows the underlying problem -- and in my view the large US external deficit associated with the United States low savings rate is still a problem -- to build.

I also identify a third risk -- well, perhaps a reality as much as a risk. Emerging market governments are likely to want to build up their holdings of US -- and also European -- equities, not just their holdings of US and European debt. China's desire to shift its portfolio away from US debt is eminently understandable. But it still raises a host of complicated issues -- issues that I fear I didn't really have a chance to fully flesh out in my testimony.

It isn't that hard to envision circumstances where China is neither willing to allow its exchange rate to adjust nor to invest all of its rapidly growing foreign assets in US debt, but the US also isn't willing to sell the assets that China wants to buy ...

More on:

Online Store

Online Store