Bad News for Pessimists Everywhere: Malthus Was Wrong

More on:

There is a tempting intuition to the idea that the real prices of non-renewable goods like coal, iron ore, or oil should rise, more or less, forever. It’s an easy argument to make, and it sounds right: The world’s population is getting bigger and bigger, so more and more goods like metals and hydrocarbons are being consumed. Every year, the sum total of what we’ve taken out of the ground mounts, never to be replaced. Supply of the stuff is limited—once it’s gone, it’s gone. So, this argument goes, as we exhaust our resources, we’ll have to mine, drill, or otherwise get our hands on it somehow but it will get more and more expensive to do so, because we’ll have exhausted the best stuff. Left to exploit ever-greater quantities of ever-more-marginal deposits, prices will rise indefinitely into the future.

Thus, in this line of reasoning, unless we start consume less of a given non-renewable material, it will forever and ever get more expensive.

The logic appears unimpeachable at first glance. But it’s wrong. The prices of raw materials have not traveled the path this story would predict for any traded commodity once inflation is factored in, over long stretches of time. One of the most powerfully counter-intuitive and empirically conclusive findings in economic history is that the real prices of nearly all major resources have actually trended lower over very long periods of time, even if they’re produced at higher and higher rates. (Oil, once OPEC got involved, is the glaring exception. But even oil prices since OPEC came about haven’t simply climbed higher and higher as global consumption has grown.) Though non-renewable commodity prices can rise steeply over years or even decades when supply and demand conditions warrant, over the centuries they’ve tended to decline after adjusted for inflation.

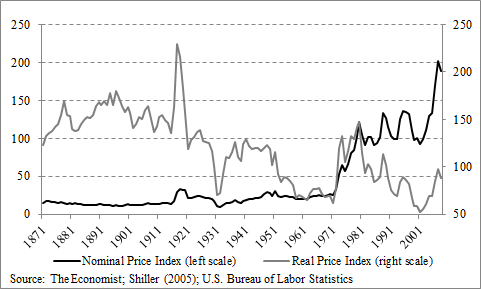

The Economist industrial commodities index, first published in 1864, is widely considered to be the world’s oldest public, regularly updated price index. Though the nominal index stretches back to 1845, data before 1857 are incomplete and data between 1857 and 1861 reflect January prices only. Only figures from 1862 onwards,which represent averages of the underlying monthly figures, are used here. They are deflated using U.S. consumer price index data since 1871, which is used in the Case-Shiller historical home price index. (The message in the data is the same regardless of whether they are deflated by the U.S. consumer price index or the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) deflator, as some prefer.)

The industrial commodity index is a better reflection of long-term trends in non-renewable resource prices than the all-commodity index, which also includes food prices, so this analysis focuses on the former index. The commodities included in the industrials index, as well as their relative weightings, have changed over time, with the current weightings reflecting the value of world imports from 2004-2006.

Figure 1. Economist Industrial-Commodity Price Index in Real and Nominal Terms (1871-2010)

The trend is clear: Raw materials prices show a secular deterioration relative to manufactured goods over long stretches of time. Since 1871, the Economist industrial commodity-price index has sunk to roughly half its value in real terms, seeing average annual compound growth of -0.5% per year over the ensuing 140 years. Even after the boom years of the 2000s—in 2008, for instance, as commodity indexes soared, the Economist index never climbed more than halfway above where it stood 163 years earlier, in real terms.

So, pessimists, rejoice: The future may be bleak, but it’s been bleaker.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store