The (almost) dollar crisis of 2007 ...

More on:

It is now rather common to argue that those economists who anticipated the crisis anticipated the wrong crisis – a dollar crisis, not a banking crisis. Robin Harding of the FT writes:

"If economists try to predict crises they will get it wrong, and that will reduce their credibility when they try to warn of risks. It was in their warnings that economists failed: plenty talked of ‘global imbalances’ or ‘excessive credit growth’; few followed that through to the proximate sources of danger in the financial system, and then forcibly argued for something to be done about it."

Free exchange made a similar point last week.

“It’s interesting that he [Krugman] mentions Nouriel Roubini, who is one of several international economists who famously saw some sort of crisis on the horizon but who very much erred in guessing the precipitating factor. I think international macroeconomists have been looking for a dollar crisis for quite some time, and they believed that such a crisis would bring on the meltdown. Instead, the meltdown occurred for other reasons and paradoxically reinforced the position of the dollar (and, for the moment, many of the structural imbalances that have troubled international economists).”

Actually, the crisis has -- at least temporarily -- reduced those structural imbalances. The US trade deficit is much smaller now than before. And, be honest, the criticism directed at Dr. Roubini should have been directed at me: after 2005, the locus of Nouriel’s concerns shifted to the housing market and the financial sector, while I continued to focus on the risks associated directly with the US external deficit. But it is hard to argue against the conclusion that the current crisis stems, fundamentally, from the collapse in the financial sector’s ability to intermediate the US household deficit – not a collapse in the rest of the world’s willingness to accumulate dollars. The chain of risk intermediation broke down in New York and London before it broke down in Beijing, Moscow or Riyadh.

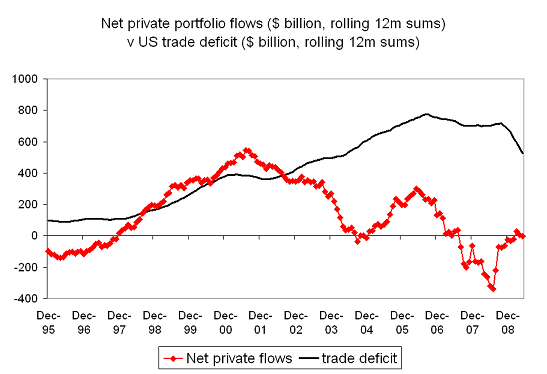

At the same time, I also think the argument that warnings about "imbalances" (meaning the US trade deficit) were wrong neglects one important thing: there was something of a balance of payments crisis in 2007, although it took a very unusual form. When US growth slowed and global growth did not, private investors (limited) willingness to finance the US deficit disappeared. Consider the following graph, which plots (net) private demand for US long-term financial assets (it is based on the TIC data, but I have adjusted the TIC data for “hidden” official inflows that show up in the Treasury’s annual survey of foreign portfolio investment) against the US trade deficit.

At the end of 2006, private demand for US portfolio investments disappeared. Net private flows, on a rolling 12m basis, went from around $200 billion to negative $350 billion. The gap between the trade deficit and private portfolio flows consequently became quite large. Close to a trillion dollars.

And that gap corresponded to weakness in one of the world’s few truly floating exchange rates (though PBoC and other big players no doubt have an impact of how the dollar floats against the euro).

What made up the gap, avoiding an outright crisis that would have forced the US to adjust far more rapidly? Truly unprecedented reserve growth – as private capital flooded emerging economies, including emerging economies with large current account surplus. That led to an extremely high level of official inflows into the US.

It is possible that the rise in official inflows drove up US market prices (and pushed down yields) and thus pushed private investors out of the US market. But the strong correlation between the fall in private demand for US assets and the dollar-euro suggest another dynamic was at work. Private investors shifted from financing the US to financing the emerging world, and emerging market governments channeled that flow back to the United States.

Nouriel and I clearly under-estimated the willingness of the emerging world to accumulate reserves and thus to finance a US deficit. Dooley, Garber and Folkerts-Landau got that right.

But the ability of the US to attract the external financing it needed to sustain its large deficit before the Fall 2008 crisis was – I would submit – a bit more of a dicey proposition than some commentary now suggests.

What did international economists and a host of others (look at the IMF’s 2007 report on the United States) really get wrong?

They thought the rise in foreign demand for US corporate bonds (a category that includes asset backed securities, including "private mortgage backed securities") meant that risk was truly being dispersed away from the heart of the American financial system. Few realized that a lot of the demand was coming from SIVs sponsored by US institutions -- and that a host of European banks with large dollar balance sheets (often managed in London) had effectively become part of the core of the US financial institutions.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store